The Club

The Droste effect or Mise en abyme––an image of an image in its image, in which that image wormholes into an abyss, recurring ad infinitum. An imperfect metaphor, but what comes to mind when I think of a club with the purview to review the London Review of Books.

The Club, while human in scale––small, personal––will be expansive of mind. It will have as little to do with computers, screens and social media ‘reach’ as possible. Like the Review it will be rooted in history, it will be decidedly untrendy. Thank god it will not be flashy or pithy. After all, reading the London Review of Books is a private, thoughtful and committed act, and the Club should reflect that.

At the end of 2019, seven years after first subscribing to the Review, it was apparent that the LRB was one of few constants in my life. As I ran the risk of losing track of myself, it reliably appeared at seven addresses from Melbourne to London to Sydney and back to Melbourne. A wellspring of information and ideas, it broadened the otherwise narrow field of trending topics toward which one can be channelled if not careful, conscious, conscientious. Dare I say reading the Review had become part of my identity.

When I was in London I would pass time in its Bookshop and Café, attend its events. In 2014 I saw Akhil Sharma and David Sedaris in conversation, and one of them, I can’t remember which, turned to the tightly packed audience sitting between the bookshelves and said something to the effect of ‘you are my people, we are a family of sorts’––a touching sentiment when you’ve outgrown the family you were born into and have been remiss to start your own. If not DNA, then what better to share than a common identity based on what is arguably the best literary journal of our time.

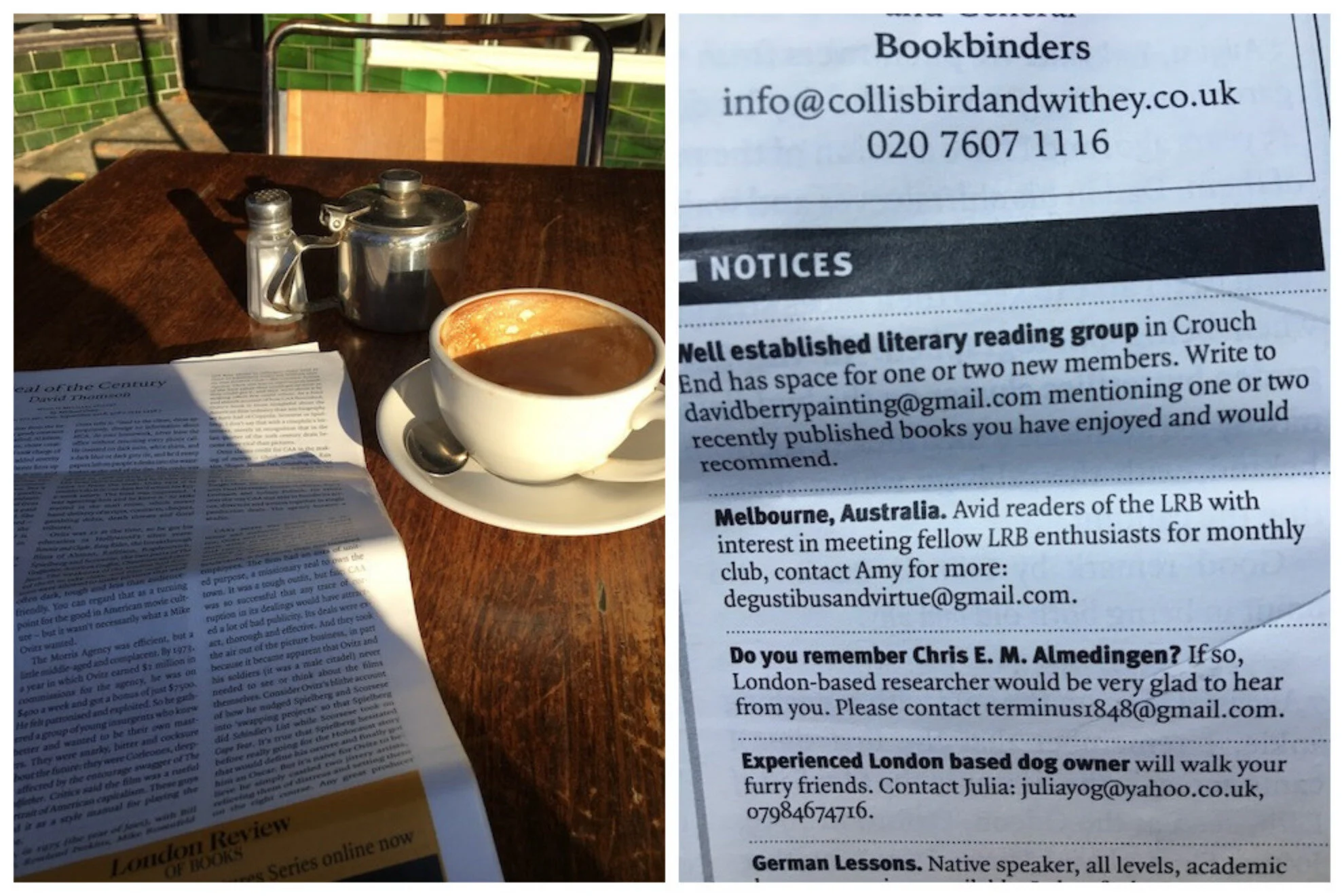

I decided to place an ad in the LRB’s famed classifieds. Not in the ‘Personals’ (Sexually, I’m more of a Switzerland), lest someone think I was suggesting a veritable orgy, but the truly neutral ‘Notices’ section. In the tradition of classified ads, I kept it short and sweet, giving great thought to the punctuation, even staying up late one night to phone Ellie in Sales to make payment.

So it was my little ad appeared in Volume 42, Number 1, the 2 January 2020 edition, on page 42:

Melbourne, Australia. Avid readers of the LRB with interest in meeting fellow LRB enthusiasts for monthly club, contact Amy for more: degustibusandvirtue@gmail.com.

Wherever I may roam…

Beyond what was said in black and white, I was looking for a few things at the time, between the lines.

Too accustomed to focussing on life’s negatives, I wanted to foreground the positive, so deepening my relationship with the LRB and connecting with fellow-feeling humans seemed like a good place to start. As a polluter I was also hoping to address my propensity for international travel.

On returning to Melbourne from a trip to Europe in October 2019, I’d declared that in 2020 I would not fly overseas. A fairly paltry assertion I was unsure at the time I’d meet, even though as a backdrop of flames blazed across Australia, it seemed the least I could do was curb my personal carbon emissions.

Without travel, and as an Australian with a global outlook unwilling to give up a cosmopolitan, international identity and transoceanic friendships and sensibilities, I knew I’d have to take personal responsibility for fulfilling my worldly urges. Luckily I (with my attendant privilege) have to hand all the tools to engage with ideas, creativity, culture, histories, hopes, horrors and art, music and film from around the world, from the comfort of home.

And just because I’m staying home, I thought, this being 2019 and all, it’s not something I need do alone. I approved the copy, paid for my ad, sat back and waited.

*

Late January 2020 I got my first response, from Joan. Then came Meredith and David, Debi and Lachlan... None knew what to expect. Some were cautious, others catalogued their reading habits by way of credentials. I had interest from a man in country Victoria and another in Brisbane.

I suggested our first meeting take place on a Saturday, in the city, at the shoulder time of 4-6pm that allows one to drink tea or wine without it being weird. We would, I suggested, get to know each other with general conversation about why the LRB; which writers and themes we find most resonant; recent issues: issues. We would also structure the session with a directed discussion and in-depth review of one selected article.

I selected ‘Vodka + Caesium’, an essay on Belarussian writer, Svetlana Alexievich, by Sheila Fitzpatrick, from Vol. 38 No. 20, 20 October 2016. I would lead the discussion.

Sheila Fitzpatrick stands out to me among many excellent writers for exposing a whole world I cannot fathom. I extract clues. She’s an Australian. Writing for the LRB, about…Russia? Russian history, politics, writers, defectors. But of course. Just because you’re Australian and you live on this island at least an eight hour flight from anywhere.

We are people of the world, we have libraries, we can read.

Fitzpatrick delivers an armchair experience of the USSR, Russia, Ukraine, etc, the GDR––East Germany––a kind of travel that has taken me to places that no longer exist, places physically and temporally inaccessible and places I’ll likely never go, not now I’m trying to be good, and definitely not now I’m not allowed.

Fitzpatrick’s piece on Svetlana Alexievich inspired me to read Secondhand Time, and her own book, Mischka’s War, which in turn led to Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse 5; to Russian film Beanpole (MIFF 2019) and HBO’s dramatisation of Chernobyl; to the Bellingcat Podcast on MH17, and to not necessarily connect all these things in the process, rather my experience of them.

Permission I felt was granted by another LRB favourite and contributing editor, Marina Warner, who wrote in a piece for Prospect magazine that the critical thinker should: “Think about how you’ve experienced this, how the words are acting upon you and why, what the writing is doing to you when you’re reading, what associations it brings up.”

Me? My experience? Warner’s was an invitation to the personal, maybe even a directive. But who was I to participate in critical thinking? Who was I to argue. It’s true I wanted to risk a critical practise, something with which I’d split after three failed attempts to engage in the university, where on the one hand there is talk of “think for yourself”, but as far as I could tell, only ever reward for regurgitation.

*

Saturday 22 February 2020, the world still seemingly normal. There were five of us around the table. No one said yes to wine, which worried me. I had notes and I felt quite silly. I introduced our subject, Svetlana Alexievich, born Ukraine raised Belarus (in what was then the USSR), studied journalism, worked as a teacher, journalist, editor. Writer of “documentary novels” at the “boundary of reporting and fiction.” She won a Nobel Prize for Literature in 2015 for books Fitzpatrick calls “collective oral histories”. Testimony.

Alexievich describes Secondhand Time as a “diagnosis of the contemporary social consciousness”, luring me in with the promise of a glimpse into something foreign I can’t comprehend: Soviet, sovok, homo sovieticus. Who are these people? How do they live? What motivates them?

In Beanpole (reviewed here in the New York Times), we are invited inside the kommunalkas, where “like the thin young nurse nicknamed Beanpole, the men and women…don’t complain or even speak much about their suffering, perhaps because it would be like describing the air that they breathe.” Air that, on account of all that communing, one suspects was cloying, claustrophobic.

The film takes us to post-war Leningrad––another non-existent destination––where we see war through women’s eyes, a perspective to which Alexievich is also committed, as for being half the story, it’s much too rarely told.

The Second Sex. Secondhand Time. This old thing? Looks familiar. Tired. Worn.

Alexievich gets people to talk. She suspects it’s because like them, she’s a sovok. She lived through it.

The Consolation of Apocalypse. That’s what she calls Part 1. I think about the word consolation…There is no prize, yet still we go to war. And what for? Capitalism keeps winning. Other ideologies come and go––religion, facism, communism––money has beaten them all. “Life is better now, but it’s also more revolting.”

Alexievich is writing what feels like a reckoning. Which is what good journalism should always be. Uncomfortable for everyone. She says of her process: “In writing, I’m piecing together the history of ‘domestic’, ‘interior’ socialism. As it existed in a person’s soul. I’ve always been drawn to this miniature expanse: one person, the individual. It’s where everything really happens.”

Yet with the personal comes tension with the group––with national and nationalistic tendencies. In an interview on freedom of speech you can find on YouTube, Alexievich says that their individual inventions remained an apparition. Unreal. They came up against “the ‘red man’, the mass person, an aggressive aggregation, a gross projection of ego” and were subsequently unable to grasp the freedoms they wanted, the way they defined them, as they looked––to them––in their own personal utopias.

It turns out each witness is unreliable for having thought that everyone shared their ideals.

Alexievich acknowledges the unreliable witness: “Their stories had nothing in common except for the significant proper nouns: Gorbachev, Yeltsin. But each of them had her own Gorbachev and her own Yeltsin. And her own version of the nineties.” Fitzpatrick goes a step further and reminds us that Alexievich herself is unreliable… Which is why her undertaking, the documentation, must be expansive, forensic, nuanced. It is only in its bigness that Secondhand Time can avoid dichotomies. No one person is good or bad, right or wrong. A reminder that if you’re reading one story it’s probably the wrong one.

Considered not exactly a history, nor a historian, on account of her handling emotion, “not just the facts”, I think while reading that surely there’s a boiling point, or critical mass at which we can accept that emotions become fact enough to be historically relevant.

“Suffering as information.”

A witness speaks: “The mysterious Russian soul… Everyone wants to understand it. They read Dostoevsky: What’s behind that soul of theirs? Well, behind our soul there’s just more soul. We like to have a chat in the kitchen, read a book. ‘Reader’ is our primary occupation… All the while, we consider ourselves a special, exceptional people even though there are no grounds for this besides our oil and natural gas.”

A witness speaks: “1960s dissident life is the kitchen life. Thanks, Krushchev! He’s the one who led us out of the communal apartments; under his rule, we got our own private kitchens where we could criticise the government and, most importantly, not be afraid, because in the kitchen you were always among friends.”

A witness speaks: “With perestroika, everything came crashing down. Capitalism descended…90 rubles became 10 dollars. It wasn’t enough to live on anymore. We stepped out of our kitchens and onto the streets, where we soon discovered that we hadn’t had any ideas after all––that whole time, we’d just been talking. Completely new people appeared, these young guys in gold rings and magenta blazers. There were new rules: If you have money, you count––no money, you’re nothing. Who cares if you’ve read all of Hegel? ‘Humanities’ started sounding like a disease.”

A witness speaks: “I’d often reminisce about our kitchen days… There was so much love! What women! Those women hated the rich. You couldn’t buy them. Today, no one has time for feelings, they’re all out making money. The discovery of money hit us like an atom bomb…”

*

In her Nobel acceptance speech Alexievich said, “We all live in the same world. It is called ‘The Earth’. A barbaric era is upon us once again. An era of power. Democracy is in retreat. I think back to the 90s…At that time, it seemed to all of us…to you, and to us, that we had entered a safe world. I remember Gorbachev’s dialogue with the Dalai Lama about the future, the end of history…”

The unreliable witness speaks.

Power, horror, does not go away. It shape shifts.

*

I ask if anyone would like a glass of wine. Everyone says yes. Either a sign that they’re enjoying this, or they can’t bear it and are too polite to leave.

I read from Slaughterhouse 5.

“‘I am from a planet that has been engaged in senseless slaughter since the beginning of time. I myself have seen the bodies of schoolgirls who were boiled alive in a water tower by my own countrymen, who were proud of fighting pure evil at the time.’

This was true. Billy saw the boiled bodies in Dresden.

‘And I have lit my way in a prison at night with candles from the fat of human beings who were butchered by the brothers and fathers of those schoolgirls who were boiled. Earthlings must be the terrors of the Universe! If other planets aren’t now in danger from Earth, they soon will be. So tell me the secret so I can take it back to Earth and save us all: How can a planet live at peace?’

Billy felt that he had spoken soaringly. He was baffled when he saw the Tralfamadorians close their little hands on their eyes. He knew from past experience what this meant: He was being stupid.

‘Would––would you mind telling me…what was so stupid about that?’

‘We know how the universe ends…we blow it up, experimenting with new fuels for our flying saucers. A Tralfamadorian test pilot presses a starter button, and the whole Universe disappears.’

So it goes.”

I think of the heroin addict, and how we’re all living a long-drawn-out suicide in real time; living in that state where a person “wavers on the edge between being and non-being.” Suicide is one thing. As the existentialists say, the absurd is another. Down here in this state we must embrace the project and do the things that must be done. Samizdat, bone records, here is where the art is, the art of living, existence. The despite which. The “thinking beyond their mourning.”

The thinking which if we cease, sees the space filled with trolls, cronies, QAnon.

The Bellingcat podcast on the downing of MH17 over Ukraine provides a perfect example of what we’re up against. Employing investigative journalism and open source research the Bellingcat collective expose what happened and the ways in which it was covered-up, not only uncovering incontrovertible proof that a Russian surface-to-air missile (a Buk) brought down the flight, but also the ways in which the Russian approach to truth has d/evolved since the dissolution of the USSR.

“Back in Soviet times Moscow tended to try and push its own answer to whatever dilemma was around. It had a clear ideological stance. It would try and convince people of its truth. But Putin takes a post-modern approach––rather than attempt to espouse a truth, he questions: ‘what is truth, will we ever know what truth is?’”

They sum up today’s political playbook as follows:

Deny everything

Offer alternative explanations

Create a confused information space

Bury the truth in as many bizarre theories as possible.

“Scramble the information space.”

In a database of nine million fake tweets seeding pro-Russian fake news, conspiracy theories and disinformation, Bellingcat researchers identified a peak of 65,000 tweets in a three-hour period on 18 July 2014, the day after the downing of MH17.

*

The HBO production, Chernobyl, opens on the subject of Truth:

“What is the cost of lies?” It asks.

“It’s not that we’ll mistake them for the truth, the real danger is that if we hear enough lies then we no longer recognise the truth at all.”

*

I look around the table. They’re not bored. Meredith, prepared, experienced, better read than the rest of us, wise, with great tempo. Alex, analytic, schooled in all the isms, speaks in full coherent sentences off-the-cuff making light work of a complex politico-historic context. Zed interjects with the Croation experience: compare and contrast. Lachlan is mainly quiet, but he’s an active listener, effusive. We’re riffing. The bottle is gone and we’re at time. I’ve lost the thread if ever there was one of what I’m saying. My contribution feels no more sophisticated than quotable quotes, and I don’t think I can see what my point is but we’re buzzing. I’m mainly imploring people to read and listen and see the things I’ve seen, cementing our fellow-feeling. And no, really, I was put off too. What’s wrong with subtitles? I don’t understand why it’s in English, just like I don’t understand why there was an English Wallander set in Sweden. But that I quickly got over it, fixated on the kind of awfully excellent televiewing experience of witnessing inefficiency and incompetence and unable to look away chanted ‘this is not good’, ‘this is not good’, ‘this is not good’ as if I could arrest something that happened back in 1986 that we full well know happened despite their best efforts to contain the truth.

We’re saying goodbye, and we’ll do it again they say, and I’ll bring wine says another. And I think this year’s going to be fine! We have our next subject. More readers have responded to the ad. Our Club meets again in a month.

Except as you know, it didn’t. And it isn’t. And while the LRB still arrives, I find myself mainly talking about the supermarket and the size and consistency of the dogs’ poos these days––on which I’ll spare you the details. I desperately need to revive my kitchen table conversation. Invite guests into my home. Club together.

I know that if conversation is all I lost in 2020 I’m on a good wicket, but I also know that without it we lose the thing that foments our art and activism. Something we can’t afford to lose sight of for long. I hope like hell I snap out of it soon.