Why philosophy?

Someone says you’re idiosyncratic. You take it as a compliment though it was delivered with indeterminate tonality. A lovely word – its Greek stems idios ‘own’ and synkrasis ‘mixing together’ – an exacting neologic combination. It's very much a mix of…

Someone says you’re idiosyncratic. You take it as a compliment though it was delivered with indeterminate tonality.

A lovely word – its Greek stems idios ‘own’ and synkrasis ‘mixing together’ – an exacting neologic combination. It's very much a mix of what are ultimately shared characteristics and peculiarities that make up a person and provide something like an identity, independent of the mass (morass). I became this idiosyncratic person by living in inner-city multicultural societies from which my mix was collected.

Naturally I, Amy Rudder, of independent and curious mind think this ‘mixing together’ is a fundamental of modern humanity and something to be celebrated. I value activity and authenticity, and having had the privilege (and the gusto to get up and go) to travel widely, I’ve learned to communicate across drawn, cultural and linguistic lines, forming opinions based on experience, not conditioning (she thinks). I want to lead by example, challenge preconceptions and instigate positive change (of course). But, to make a meaningful impact as an individual, emotional and mental strength (and stability) are important. The pursuit therefore of a more refined thinking – to order and organise – is to understand and overcome what can sometimes be an overwhelming torrent of thoughts and ideas. When the very things I/we think can destabilise, we’re far from able to contribute even in the smallest of ways, making values (for all their merit) mere sentiment.

Professionally (in the context of 'the office' as workplace), I'm sufficient. I have somewhat commercially viable analytic, strategic, administrative, project management and communication skills. I’m a generalist, favouring an emphasis on techniques and methodology applicable to numerous subjects. With a 21st century (a priori) awareness of ‘knowledge’ (and google a click away) I can canvas and consume large quantities of information, synthesise ideas, and convey them concisely to a prescribed audience.

Big whoop.

Grinding out and graduating with a Bachelors in communications in 2000, it took 15 years of living to identify a field for focussed, Masters study which feels every bit a necessity, now.

In between came life (good and bad) and a whole heap of listening, reading and writing. Over time, my interests continued to gather in the philosophical disciplines (predominantly existentialism and ethics – I didn’t know what phenomenology was back then and didn’t know yet to recognise it). Guided by the steady and thorough approach of Joe Gelonesi on the ABC Radio National show, The Philosopher’s Zone, my interest in public things, thinking and politics was reignited after the decade prior had seen me stuck in a sort of post-millennium apathy. My cherished subscription to the London Review of Books also played its part; the prevalence of thinkers producing quality writing, and writers producing quality thoughts, something of an epiphany to this one-time cynic of all things remotely academic.

I guess there are parts of my story that have been predictable. I’ve been at times engaged, serious, militant, disillusioned, bored – ‘give a fuck? As if I give a fuck!’ I’ve taken an interest in politics, policy, people and I’ve dumped them all. I’ve escaped for the arts, only to use art as a medium for understanding political and philosophical systems, and as an avenue for meeting the challenges of cultural communication. Like critical thinking, art is important in personal examination and progress, and a fantastic antidote to the banal. Creating something telling or intriguing from the pragmatic trappings of existence is a conscious act and requires an engagement with the world around us. For me, it marked a return to the very frictions of political and societal complexities I’d tried for a time to avoid, but found impossible to ignore.

As a writer, my role might be to extract and concoct a bit of truth by borrowing words from those deeper and funnier and images from scenes lighter and darker, smashing them together to create an interesting, accessible, (and if I do it right) recognisable/truthful/real other. So I observe and preserve, filling notebooks and napkins with an obsession for story, relationships and risk-taking. And if I consider fiction an art (which I do), it sits alongside and is necessarily informed by the other arts. A ‘beat’ in a script where you witness nothing acted into being, an all-consuming orchestral crescendo, the precision in a painted surface, all influence the material, the form; which is not to say it’s in any way formulaic. The realm of ideas is nowhere near that safe. Perhaps with the exception of the stoics, people of ideas inhabit the arena of risk; an artist’s interpretation of ideas – a pretext to the art – a very real, very public or personally confronting commitment to questioning the status quo.

For the egocentric (I’m in recovery), this feels important.

Egoism made me bold, but also left me flat. The very thing that led me to feel, has led me to feel responsible, and more often than not, irresponsible, for what could have better been me/my/mine (yes, I thought too often about me). So thank goodness for the absurd, for Dario Fo (Grammelot), for Camus (Sisyphus); for Chris Marker – what is he talking about? This conquering?

I dare say it may be love… Yes, it may well be love that saves us. And in the absence of love – philosophy that fills us, art that stimulates, words that resonate.

In a modest city art space I co-founded and that opened to the public in 2011, we showed Lani Seligman’s neon work ‘Yes, but’ on which I wrote at the time:

“…like a billboard [it] demands attention, but unlike everyday advertisements has an alternative agenda. The affirming proposition has a sting of uncertainty in the tail which better echoes reality. Decisiveness is so rarely black and white. ‘Yes’ is just a word – an antonym to ‘no’ – and so lacking in the complexities we often want, or need to convey. Complex, contradictory answers are the stuff of humans. As is our eagerness to please. It is within this context that the artist confronts our idle ‘yes’ and asks us to defy and redefine our easy willingness.”

It just so happened that when she proposed the work I was reading Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls. And there, in the text, was the following:

“…he realised that if there was any such thing as ever meeting, both he and his grandfather would be acutely embarrassed by the presence of his father. Anyone has a right to do it, he thought. But it isn’t a good thing to do. I understand it, but I do not approve of it…But you ‘do’ understand it? Sure, I understand it, but. Yes, but. You have to be awfully occupied with yourself to do a thing like that.”

Ego. Suicide. Absurdity. Absolution.

The religious doesn't feel that far away. Yet it never rang true. For me, art, philosophy – even fantasy is a better fit.

It was Hanif Kureishi’s The Black Album that made me realise I was once left for an eggplant, and though a massive blow to the ego, it shocked and tickled in equal parts. I later learned that Kureishi studied philosophy. In retrospect, I can see his capacity to be both reflection and antagonist of the zeitgeist, rooted in such studies.

I continue to explore ethics, philosophy of mind, despair and resistance, as well as the shift in epistemological value over the last few hundred years. In a country where thinking seems undervalued, I often feel the need to leave to do just that. When I read repeated reports of Australia’s disregard for its Indigenous population and asylum seekers it is with head in hands for our ongoing squandering of opportunity in the face of good fortune that self-imposed exile feels necessary, even if of no consequence to the unwitting fools who have driven me away.

Despite my desire to leave it all behind, I remain invested in Australia… there is too much in me that is Australian to ignore. But I’m other things too. I’ve been called idiosyncratic, wild, sensitive, heroic. I like to think I’m principled, resourceful, intuitive. I am a sucker for adventure. I am for outsider art. I am for the cause of women – for women to be free to follow their dreams on their own terms – to be seen, to be heard, to have opportunity and respect. I am a feminist. I can be moody, snobby, judgemental. I am ridiculously skilled at navigating. At ground level, I simply cannot get lost. But up in my head? Well, that’s a different story.

Yes, But by Lani Seligman and The Black Album by Hanif Kureishi.

Something like a phenomenon

To date this piece, I write at the time of the worst ever domestic shooting in the US. Which at the time you’re reading, may not be the worst anymore. As it is, I’ve got 49 dead, 53 wounded.* What have you got?

To date this piece, I write at the time of the worst ever domestic shooting in the US. Which at the time you’re reading, may not be the worst anymore. As it is, I’ve got 49 dead, 53 wounded.* What have you got?

If, phenomenologically, I feel my way through the news as it is, it feels pretty shit. Get bogged down in causal categories of history, psychology, sociology – it’s shitter still. Project into the future, and I'm inclined to the morose, musing what’s it all for (this thing called life) when it’s only getting worse? So phenomenology – the dealing with the phenomena – the things, objects, people, affects as they are, now has its appeal even if only as the best of a bad bunch of ways to work through the world as it is for us, now.

The existentialists, confronting existence and engaged in a life-long, laboured search for meaning, rely on phenomenological experience as some kind of consolation to the delayed gratification of death. In the long interim called life, in which we inhabit a body, some decamp to nihilism, some to absurdity (which is possibly just an optimistic rebranding of the former). And so it is, without a more appealing alternative, accepting the absurd and embarking on the existential project has become a way of experiencing, interpreting, advancing, and at times transgressing the world as I’ve found it.

The present of a person reading this essay will occur in an infinite now. This text will appear as a collection of letters which I ask you to confront in the spirit of phenomenology. In so doing you’ll find clues to the direction of my philosophical inquiry, a methodological approach to my thinking, and a determined effort to overcome cynicism by subsuming resonance from other people’s projects, using the momentum to run interference of my own. So come closer, join me.

I’ve done my time from afar. I’ve lived and read, and as I’ve read – as a woman – I’ve been disinclined to fret about the universal use (I’m being generous) of ‘man’ for human, of which I, as woman am part. The overwhelming abundance of man/he/himself/his has in fact helped me maintain a distance from which I can think abstractedly about what I read, to learn in isolation from the encumbered self. So finding a way for it to suit me somewhat (possibly the worst kind of collaborator) I hadn’t previously taken up a political or feminist stance on the issue, choosing to see it (even defend it) as a linguistic device deployed for the sake of simplicity. But now I have my grounding, I’m ready to move past abstracts and dive in.

Where I now encounter/perceive the use of man/he/himself/his as simplistic, thoughtless, anachronistic or lazy and not necessary to denote the male in opposition or exclusion to the female, I alter it to read respectively, the personally relevant woman/she/herself/her. This way, I have begun to bridge the gap that remains between the ideas and my prescribed and identified female self. But this personal project must become more than a private habit and more broadly influence the feminist linguistics project which certainly is political in its pursuit and potential to better the world (and which may be surpassed by a circling trans-linguistic theory before it’s fully realised – all the more luck to it!).

I want to be clear men are not the problem (she tells herself). I am a prolific reader, supporter and believer of the many men who know what to do with their manhood. The problem is privatisation, professionalisation, industrialised military and security, and the stranglehold capitalism and the corporation has on government, the judicial system, media and religion. The problem is that all these things are inherently mean and nasty. And it just so happens, in the western-historical tradition, they’re problems most commonly peopled and propelled by men. Granted, it’s for the same western-historical reason that men have led much of the critique and resistance (and which possibly explains why the revolution has never looked quite different enough to effect change).

From within the university, a one-time fertile place for freedoms and possibility, the view is similarly bleak. In an update of Michel Foucault’s ‘disciplinary societies’, which mapped the penetration of panoptic- and bio-power into everyday life, Gilles Deleuze stresses a more invasive shift to complete control: ‘just as the corporation replaces the factory, perpetual training tends to replace the school, and continuous control to replace the examination. Which is the surest way of delivering the school over to the corporation.’

Infantalised, (the irony being we pay for this patronage) we can abide by the fantasy, fight it, flee or free-fall between the gaps to Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s ‘undercommons’ of the university. They write: ‘it cannot be denied that the university is a place of refuge, and it cannot be accepted that the university is a place of enlightenment. In the face of these conditions one can only sneak into the university and steal what one can. To abuse its hospitality, to spite its mission, to join its refugee colony, its gypsy encampment, to be in but not of – this is the path of the subversive intellectual in the modern university…The subversive intellectual came under false pretences, with bad documents, out of love. Her labour is as necessary as it is unwelcome. The university needs what she bears but cannot bear what she brings. And on top of all that, she disappears. She disappears into the underground, the downlow low-down maroon community of the university, into the undercommons of enlightenment, where the work gets done, where the work gets subverted, where the revolution is still black, still strong.’

In a country that is not my own (the UK), I’m begrudgingly welcomed on account of my money, my pink complexion, and my capacity to perform all manner of box-ticking tasks. I wish I could be, I know I should be, but I’m not happy. Like other performances, I hoped there was a threshold beyond which (striving) would end and the real project (living) would begin. To save being sucked into permanent performance I think of Roberto Bolaño’s ill-prepared protagonist – and narrator of his short novel, Amulet – Auxilio Lacouture. Her story unfolds in the 12 days she’s alone in a bathroom at Mexico’s National Autonomous University during the 1968 army occupation. Strange to look to a fictional character with few teeth left in her mouth and little flesh on her bones for inspiration, but her unshrinking honesty, precariousness and jouissance despite it all, are refreshingly real.

On leaving her native Uruguay she recalls: ‘one day I arrived in Mexico without really knowing why or how or when. I came to Mexico City in 1967, or maybe it was 1965, or 1962. I’ve got no memory for dates anymore, or exactly where my wanderings took me; all I know is that I came to Mexico and never went back…Maybe it was madness that impelled me to travel. It could have been madness. I used to say it was culture. Of course culture sometimes is, or involves a kind of madness. Maybe it was a lack of love that impelled me to travel. Or an overwhelming abundance of love. Maybe it was madness.’

In the poetry of the sad, desperate, young Mexican poets, she seeks and finds her figurative reflection. She also finds herself literally, tragi-comically on the toilet – underwear around her ankles, reading the poetry of the melancholic Spanish exiles she admires – as the army invades.

‘I am the mother of all the poets, and I (or my destiny) refused to let the nightmare overcome me. Now the tears are running down my ravaged cheeks. I was at the university on the 18th of September when the army occupied the campus and went around arresting and killing indiscriminately. No. Not many people were killed at the university. That was in Tlatelolco. May that name live forever in our memory! But I was at the university when the army and the riot police came in and rounded everyone up. Unbelievable. I was in the bathroom, in the lavatory on one of the floors of the faculty building, the fourth maybe, I’m not exactly sure. And I was sitting in a stall, with my skirt hitched up, as the poem says, or the song, reading the exquisite poetry of Pedro Garfías, who has already been dead for a year (Don Pedro Garfías, such a melancholy man, so sad about Spain and the world in general).’

And as the soldiers search the university and the first day of the occupation comes to a close, she declares: ‘I knew what I had to do. I knew. I knew that I had to resist. So I sat down on the tiles of the women’s bathroom and, before the last rays of sunlight faded, read three more of Pedro Garfías’s poems, then shut the book and shut my eyes and said: Auxilio Lacouture, citizen of Uruguay, Latin American, poet and traveller, resist.’

Her experience is truly and fantastically devastating to aspirations of order and reason which, frankly, have failed to combat or explain the ridiculousness of reality. Her resistance is as much a testament to accepting this fact, as it is an embrace of chaos. I say this as someone whose inherited, intellectual framework is distinctly Kantian. I love a category. Like ‘cleanliness is next to godliness’, organisation is the closest I come to religiosity. I’m so inclined to the theoretical foundations of ‘practical reason’, I consider it a given and tend to dismiss Kant as a result; for what is a given doesn’t need an author or a grand design. Surely, along with other chromosomal information, it was deposited from my family into my very being...

But to excel at the application of the rational is to eventually nullify the individual. The hyper dialectic of the malleable rationalist is a conversation with myself where I argue all sides; over time, becoming so convincing at playing the different parts – seeing every point of view – my personality becomes disembodied, distanced, and argument and counter argument reduced to formula, detached from their substance or sensory tenor.

‘The surrender of woman’s thinking to rationalism and of her artifice to technics have consequences which console woman with the feeling that she is progressing, but make her neglect or deny fundamental forces of her inner life which are then turned into forces of destruction. “The sclerosis of objectivity is the annihilation of existence.”’ (Mairet/Jaspers)

…that was then.

Life’s not like that. After all, how does Kant help us make ‘individual human decisions’? And where will ‘detached deliberation’ get us? The critical dilemmas for an individual can’t be solved with the facts and laws of how to think through them. Resolution comes from ‘conflicts and tumults in the soul, anxieties, agonies, perilous adventures of faith into unknown territories.’ (Kierkegaard)

The first revolt (already an atheist) has therefore been against myself. My life was ‘pitched into the drift of phenomena’ where, abandoned, ‘the only hope for woman lies in her full realisation and acceptance of the truth [that that’s the way it is]…her personal fate is simply to perish, but she can triumph over it by inventing “purposes”, “projects” which will themselves confer meaning upon the self and the world of objects…There is indeed no reason why a woman should do this, and she gets nothing by it except the authentic knowledge that she exists.’ (Heidegger/Jean-Paul Sartre)

Existence can be a challenge when building an identity from the ground-up, inside-out, rather than opting for a ready-made. Thrust into uncertainty as the process plays out, despair can circle, as: ‘not many are capable of authenticating their existence: the great majority reassure themselves by thinking as little as possible of their approaching deaths by worshipping idols such as humanity, science, or some objective divinity.’ (Mairet)

Equally unmoved by Dawkins, Beyoncé and ‘God’, I’m happy to accept that ‘woman is nothing else but that which she makes of herself.’ (Sartre)

But bearing the responsibility of working out what that ‘else’ is, a detour via nihilism is an unsurprising turn, and for Nietzsche in The Will to Power, completely necessary: ‘because the values we have had hitherto thus draw their final consequence; because nihilism represents the ultimate logical conclusion of our great values and ideals – because we must experience nihilism before we can find out what value these “values” really had – we require, at some time, new values.’

Wise words. I lived for a time in a share house where amid the unpaid bills, tacky magnets and cleaning rota, the fridge bore a sticker: ‘try being informed instead of just opinionated.’ Philosophy (for the etymologists, philosophia – Greek, love of wisdom), may prove useful in this pursuit: to research, unearth and re-evaluate ideas. Plotnitsky writes that philosophical confrontation: ‘entails an affinity and alliance with chaos’ so as to confront mere ‘opinion’ which serves only ‘to protect us from chaos’.

We live in an age of opinion, which at one time I lauded as egalitarian. But ideas that bounce around between various opinions cannot be changed by those opinions. Opinions only add noise to the chaos, whereas: ‘philosophy engages with chaos through the creation of concepts and planes of immanence; art through the creation of sensations (or affects) and planes of composition; and science through the creation of functions (or propositions) and planes of reference or coordination.’ (Plotnitsky)

Phenomenology, a confrontation of perception, not preconception, could help put opinion to one side, forcing a pause, which unlike mindless opinion, over-thinking (a tendency of mine) or random acts, provides the time for philosophy to enact an idea.

All ideas? In any situation?

I’ve asked myself the same questions. Alain Badiou’s ‘philosophical situation’ favours the ‘incommensurate’ over the ‘commensurate’, citing the incommensurate as one where there’s a choice: ‘philosophy confronts thinking as choice, thinking as decision. Its proper task is to elucidate choice. So that we can say the following: a philosophical situation consists in the moment when a choice is elucidated. A choice of existence or a choice of thought.’ To situate, or measure the gap in the incommensurable: ‘we must think the exception. We must know what we have to say, about what is not ordinary. We must think the transformation of life…[and we must do so] against the continuity of life, against social conservatism.’

The distance between power and truth can be traversed by philosophy without devolving to opinion (which given it thrives on volume and exposure is even more dangerous when pronounced by the wealthy and privileged). Echoing Zizek’s ‘false alternatives’ Badiou outlines where he can and cannot do more than opine. An election, for example: ‘does not create a gap, it is the rule, it creates the realization of a rule.’ It’s institutional. A government and its opposition are commensurable, and therefore isn’t ‘a situation of radical exception’, and elections by turn, no turf for the philosopher. I want instead to debate the terms of the election, its currency, its potential, its evolution (and subsequently – revolution). This could explain how I turned away from politics as it is, while remaining political. The something more than it is, is posited within the ‘project’, and though my project doesn’t resemble a campaign, it is inherently political in a way that can’t be institutionalised or owned by any single interest group.

A revolt that resists both nihilism and opinion can be hard going. Like Albert Camus I’m inclined to ‘the meaning of life [as] the most urgent of questions’, but paradoxically, given it’s the great unanswerable, the more difficult thing to do is judge ‘whether life is or is not worth living’ without the definitive (or a priori) rights and wrongs to guide us.

‘Living, naturally, is never easy. You continue making the gestures commanded by existence for many reasons, the first of which is habit. Dying voluntarily implies that you have recognized, even instinctively, the ridiculous character of that habit, the absence of any profound reason for living, the insane character of that daily agitation, and the uselessness of suffering.’ (Camus)

But this isn’t an invitation to give up. Quite the opposite. The optimistic spin Camus and Sartre gave existentialism (the absurd, coffee) is naturally appealing and an improvement on the alternatives (suicide, fascism). For Camus, the ‘divorce’ between ‘the person’ and ‘their life’, from the most testing to the most banal of circumstances, is ‘the feeling of absurdity’ and he suggests that like war, the absurdity of life cannot be negated: ‘One must live it or die of it. So it is with the absurd: it is a question of breathing with it, of recognising its lessons and recovering their flesh. In this regard the absurd joy par excellence is creation. “Art and nothing but art,” said Nietzsche; “we have art in order not to die of the truth.”’

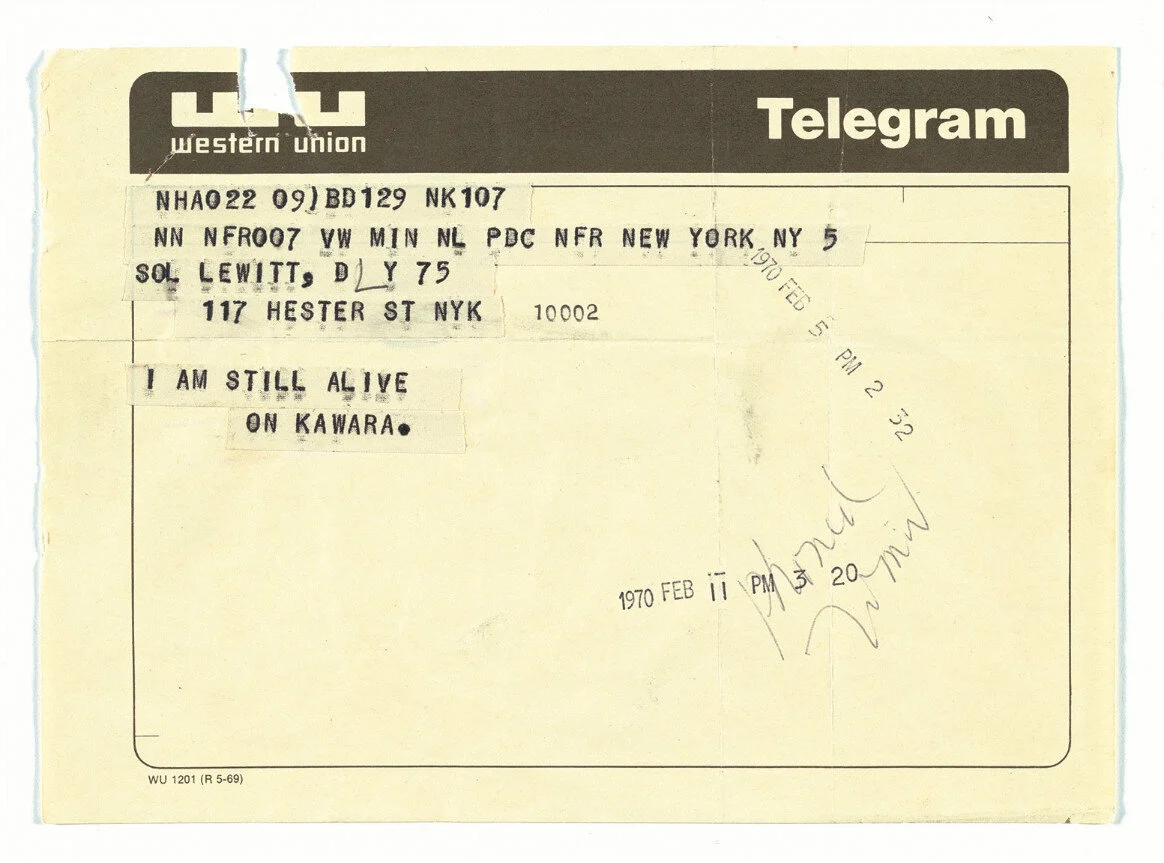

And the truth is we will die. Japanese conceptual artist On Kawara passed away in 2014. In 2015 the Solomon R. Guggenheim Gallery, New York staged a survey of his life’s work. Unknown to me at the time, I entered the gallery off ice, salt and mud strewn streets for the swirling architecture, the promise of Kandinsky’s Reifrockgesellschaft, and central heating.

fig. 1

What I got was much, much more. Over a year since, I’m still intrigued by my encounter with On Kawara’s body of work, back tracking through exhibition ephemera and show catalogues for clues to his life and reasons why it has struck such a chord. For an artist of whom there’s no picture, he’s more familiar to me now than the over-saturated Andy Warhol. Having moved to New York in 1965, Kawara’s practice unfolded in the same place and similar period as the savvy pop-artist (whose work I also admire, but for very different reasons). Eschewing photography and video, Kawara instead marks the boundaries of his body through an ongoing project of presence.

The Heideggerian Dasein comes to mind; the term a German construction of da (there) and sein (being), tidily combining notions of existence, in time, spanning Heidegger’s humble ‘thatness and whatness’ and Hannah Arendt’s assessment of Existenz, of which she says: ‘we are all ourselves little Gods after Heidegger.’ I don’t disagree with Arendt. The God complex poses a challenge, particularly when combined with dog-eat-dog capitalism, and people who equate more money with ‘more right’, but Heidegger proposed something altogether more grounded:

‘Not only does an understanding of Being belong to Dasein, but this understanding also develops or decays according to the actual manner of being of Dasein at any given time; for this reason it has a wealth of interpretations at its disposal. Philosophical psychology, anthropology, ethics, “politics,” poetry, biography, and the discipline of history pursue in different ways and to varying extents the behaviour, faculties, powers, possibilities and vicissitudes of Dasein…The manner of access and interpretation must be chosen in such a way that this being can show itself to itself on its own terms. Furthermore, this manner should show that being as it is at first and for the most part – in its average everydayness.’

The everyday was something Kawara lived with unusual commitment. In his Date Paintings (the Today series), and companion series – I Went, I Met and I Got Up At, Kawara meticulously makes traces of his everyday existence. His long-running series I Am Still Alive, consists of telegrams sent from the many, many places to which he travelled, conveying the single statement to friends: ‘I am still alive’.

fig. 2

This alternative, experimental biography ‘relies on an objective sensibility, not an analytic one: no attempt is made to register impressions, anecdotes, opinions’ which like phenomenology ‘declines to explain the world, it wants to be merely a description of actual experience. It confirms absurd thought in its initial assertion that there is no truth, but merely truths.’ (Camus)

Situating his broader practice at ‘the exact point of intersection between the objective and the subjective’ (catalogue) I’m inclined to draw parallels from this midpoint to the territory, long-revered in Buddhism, of the middle path – of mindfulness – where the reconciliation of dualisms occurs in the relationship between the self and the external world, in a balance between the two.

Growing up in a timezone more closely associated with Asia, and in a time period when those immigrating to Australia came mainly from the Asian continent, my influences and subsequent outlook angle as tangentially East as they do West – perhaps explaining something of the resonance with and recognition of this space. Meditation has helped put the body back into I am, in an attempt to recover from the mind/body split. There is no art form as potentially effective as dance to do the same. German choreographer, Pina Bausch is described as creating contemporary dance pieces: ‘that deal with those basic questions about human existence which anyone, unless she’s merely vegetating, must ask at least from time to time. They deal with love and fear, longing and loneliness, frustration and terror, man’s exploitation of man (and, in particular, man’s exploitation of women in a world made to conform to the former’s ideas)…’

But even dance has been subjected to rules, and is at risk of becoming a formulaic, constrained ‘performance’. In an interview, Bausch asks: ‘Why do we dance in the first place?’ And warns: ‘There is a great danger in the way things are developing at the moment…everything has become routine and no one knows any longer why they’re using these movements. All that’s left is a strange sort of vanity which is becoming more and more removed from actual people.’

Less interested in how people move, Bausch focused her attention on what moves people – allowing the body to speak. Contrary to criticisms of phenomenology’s introspection, new methods of connection and communication support the potential for phenomenology to promote action and agency. Merleau-Ponty metaphorically links the ‘synthesis of one’s own body’ to our perceptive faculty and Leder expands on the binding capacity of ‘phenomenological vectors’ linking their function to a method of meaningful engagement with the world. As Plotnisky points out: ‘There is no concept with only one component. Each concept is a multi-component conglomeration of concepts, figures, metaphors and so forth which, however, have a heterogeneous, if interactive architecture rather than forming a unity. Concepts are junctures rather than sums of parts. They are forms of vibrations and are defined by resonances, through which they may amplify or temper each other.’ (after Deleuze and Guattari)

At each juncture, there’s a fork in the ontological source code: ‘Resonance frequencies of a given conceptual system may be “awakened” by a driving force coming from another system or two such systems may be in resonance. This is, again, an interference-like process which makes the systems “vibrate”; makes them literally more “vibrant” in a convergent or divergent fashion.”

Vibration might well describe what I felt when reading Roberto Bolaño, when faced with On Kawara’s artwork, and while watching dance choreographed by Pina Bausch. A serious defence of ‘the vibe’ suddenly doesn’t seem so absurd. The much-loved 1997 Australian film, The Castle, includes a courtroom scene where protagonist Darryl Kerrigan’s hapless Barrister gives an often-quoted closing speech in support of his client’s submission to save his house from an airport expansion project.

Hapless Barrister: ‘It’s the constitution, it’s Mabo, it’s justice, it’s law, it’s the vibe, and ah no that’s it, it’s the vibe.’

[A beat.] ‘I rest my case.’

Darryl Kerrigan: ‘That was sensational.’

The argument is surprisingly effective, with the judge ruling in their favour, Kerrigan king of his ‘castle’.

Another closing speech – in which I’d make the case that the first thing I must do to implement my philosophical methodology is live. And to be alive is to continually question and create meaning for myself. By adopting a phenomenological posture I avoid over-thinking and prejudice, and provide the optimum conditions for the necessary resonance to take affect. The interference may be uncomfortable and the result, a wholesale shift in understanding, but on the flip-side, it could be thoroughly pleasant and the project a success. While I work on it, let’s just say I see things how I see things, and I call it how I see it, and how I see it tomorrow may change from today, but tomorrow when I see it, well – stay tuned…

Notes:

*12 June 2016, Pulse nightclub, Orlando, Florida. May the 49 killed rest in peace; may something be done about guns.

As Rage Against the Machine sang in the 1998 track No Shelter: ‘The front-line is everywhere.’

Sartre defends the existentialist movement as humanist on account of the political and religious ambiguity of existentialism. Due to its indeterminate nature, it provides a forum for people from all quarters to meet and discuss human problems of primary importance and common concern.

Reifrockgesellschaft might sound like a track by Rammstein, but translates as Group in Crinolines.

From the foreword to an On Kawara exhibition catalogue: ‘No artist’s statement here, as ever, no portrait of the artist and no interview.’ (Gautherot and Watkins)

‘Dostoevsky once wrote “if God did not exist, everything would be permitted” and that for existentialism is the starting point.’ (Sartre)

Unlike Daniel Dennett’s negative assessment of introspection (‘failures of imagination’) I’m inclined to liken it to the calm before the storm – as a necessary and valuable component of the storm itself.

And if it is absurd, may I defer to Camus…‘I draw from the absurd three consequences which are my revolt, my freedom and my passion.’ (Myth of Sisyphus)

fig.1

Vasily Kandinsky

Group in Crinolines, 1909, Oil on canvas

37 1/2 x 59 1/8 inches (95.2 x 150.1 cm)

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection

© 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

fig.2

On Kawara

Telegram to Sol LeWitt, February 5, 1970

From I Am Still Alive, 1970–2000

5 3/4 x 8 inches (14.6 x 20.3 cm)

LeWitt Collection, Chester, Connecticut

© On Kawara. Photo: Kris McKay © The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

The terrific périphérique

When underwear shopping, try as I might to avoid it, there’s always that moment I inadvertently find myself in the big-bosom brassiere aisle. A teenage boy or young girl I’d understand, but me, a grown woman? I panic, blush…

When underwear shopping, try as I might to avoid it, there’s always that moment I inadvertently find myself in the big-bosom brassiere aisle. A teenage boy or young girl I’d understand, but me, a grown woman? I panic, blush. Small-of-breast I’m guilt-ridden for being where I shouldn’t. I fear being seen and judged: creep, deviate, voyeur! And every time, despite being a woman, just like our teenage boy or younger girl might, I wonder what it’s like to fill that void in those handfuls of fabric – DD, EE, F, G! The mind boggles. That large-breasted person is a woman too, yet she and I who have this word in common, couldn’t be more different – and that’s just to start.

Despite societal, political and capital forces working to narrow the definition and do away with difference, I am for the potential of that signifier: woman, to elicit the broadest possible spectrum, expression and manifestation of traits, behaviours and physical features; for the word to serve as a practical point of departure only, everything else – the myriad adjectives at our disposal – a celebration of our diversity. While those with vested interests may feel the need to translate linguistic simplicity into applied simplicity, limiting woman to any one interpretation is to risk a restriction in rights, recognition and individual agency.

The centre is unsustainable, prone to stagnate and misanthropic in its blind pursuit of uniformity. Centripetal forces, like a mass media, central government and monotheistic church dictate this perpetual march toward the middle, and its middling same-ification. The constraints and confines of the centre require identifiable and thereby manageable traits; constant refinement (distillation) resulting in a space simply too small to cater to a people naturally inclined to growth and reproduction. Thankfully, control of the future is finite, and any safety inherent in an existing consensus will eventually be disrupted by a progressive progeny, that like the throwback, alerts us to a dormant recognition, not – in this instance – of the recurring similarities, rather the explosion of possibilities evolution allows.

There have always been individuals who take their role seriously, pushing at the periphery and thereby widening the space in the centre for those of us seemingly more simply divisible (into man/woman, boy/girl). These individuals are increasingly important in a world which on the surface has sold us the idea that ‘anything goes’ while trying to categorise (limit?) all the same. Unwilling and unable to comply with the terms and conditions of inclusion, South African athletic champion Caster Semenya, and Laurence Alia – fictional antihero of Xavier Dolan’s feature film Laurence, Anyways – are two who prove that as yet, ‘anything goes’ is definitely not the case.

In 2011, Rise Films produced a documentary for the BBC covering Semenya’s reaction to and recovery from the testing and persecution she was subjected to after winning the 800 metres at the 2009 World Athletics Championships in Berlin. Too Fast to be a Woman: The Story of Caster Semenya includes interviews with the athlete, members of her family, representatives from the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF), her legal team, sport science professionals, coaching staff and peers. It confronts speculation surrounding Semenya’s gender, her ban from competition, and eventual reinstatement after a belligerent IAAF conceded she was eligible to run as a woman, as she wasn’t – as they suspected – a man. Beyond their invasive ‘scientific’ investigation, there is more compelling testimony that sheds light on matrilineal, existential and behavioural perspectives. Semenya’s mother: ‘I gave birth to her, and as a mother, know that she’s a girl not a boy’. Her coach: ‘if Caster believes she is female, she is female’. And Semenya herself: ‘what makes a lady? Does it mean if you’re wearing skirts and dresses you’re a lady? No. What kind of a lady is that? Yeah I’m a lady. There’s nothing I can say, yes I’m a lady. I have those cards of being a lady.’

Disinclined to skirts and dresses, I couldn’t agree more.

I’m not so much interested in the scientific debate, or whether Semenya is indeed ‘fully female’, as I am in looking at what ‘fully female’ might mean to begin with, not least for Semenya, but for all women, and subsequently our companions in this species we call humankind – men. With seven billion human variants and counting, and the genome code, DNA, RNA, rhizomes and chromosomes playing their part in ways to which few can testify any in-depth knowledge, it’s risky to clutch at throwaway terms that carry more meaning and power, because in the wrong hands – as power is prone to congregate – classification and subsequent claims of superiority are likely to victimise those seen by the majority, as different. Dr Gerald Conway, the Lead Endocrinologist at University College London points to one misleading example – hormones – the ‘male’ hormone, testosterone, having been a point of great contention in Semenya’s case: ‘We all have differences in our hormone levels’ he says. ‘In our gender assessment of ourselves, we’re all on a spectrum, and there’s probably no such thing as a 100% male and 100% female.’ Further, the idea and pursuit of being ‘fully’ anything points to metaphysical flaws in common thinking and exposes the vestiges of a superstitiously religious populace. If we’re to pursue a godly transcendence, a perfection, what of woman for whom the task is impossible – god as imagined in the West a distinctly male character; and what of the average man – who lets face it is a million miles from living up to Leonardo’s Vitruvian model.

Both Athletics South Africa (ASA) and the IAAF conducted tests on Semenya, (the ASA obfuscating the nature of and reason for the tests). The documentary claims they failed in their duty of care to Semenya, mishandling the case from the outset. They made no effort to protect her from the perception she had, at the least, a ‘disorder of sexual development that gives her an unfair advantage on the track’ or at the most extreme, covered up the fact she was a man, and was therefore a cheat. Conway concedes: ‘If you’re going to set competitors against each other, then you need a set of rules to decide what’s a fair competition and what’s not a fair competition.’ Fair enough. Maybe. A contradiction, actually. Competition suggests a winner and a loser. To a degree it operates outside of what’s fair. Certainly as Conway says ‘more testosterone would be a biological advantage’, but so would longer legs, bigger muscles, lower BMI, faster reflexes. South African sports scientist Professor Tim Noakes asks: ‘What about a male who has a biological advantage…? We call him Usain Bolt. This man Usain Bolt is a complete biological freak. There’s never been an athlete like him. So he’s genetically different. But do we expel him? No! We say he’s the greatest athlete ever... But when a female comes along, we say no, no she’s abnormal we’ve got to kick her out. That’s the whole point of sport. The best are genetic freaks.’

Giving the John Peel Lecture for BBC Music in 2015, Brian Eno gave his definition of art as ‘everything you don’t have to do’. In which case, it included once, sports. We ran. Certainly we ran fast if we could to avoid lions, hyenas and the like. But as for the first running race? It sounds like play to me. Just like we play games, we ‘play’ to our strengths and eventually we may play to win, but using the example of dance – an art form that involving the body crosses borders between art and sport – Eno quotes from Barbara Ehrenreich’s book Dancing in the Streets... where witnessing spontaneous dancing rippling through the streets around Carnivale, she writes: ‘There was no point to it, no religious overtones, ideological message, or money to be made...just the chance...to acknowledge the miracle of our simultaneous existence with some sort of celebration.’ Which is possibly how running felt for Semenya when she first started playing soccer with the boys, preferring it to the ‘typically feminine’ activities of her female friends. Later though, when there was money to be made, everything changed. Hardly the first tomboy – but a successful one for sure – rejecting a ‘feminised’ role had an affronting effect.

French philosopher, Luce Irigaray connects societal anxiety of this kind to the disruption of the entrenched trope of woman as commodity. ‘In our social order, women are ‘products’ used and exchanged by men. Their status is that of merchandise, ‘commodities’. In her work This Sex Which Is Not One she breaks down the component parts: ‘A commodity – a woman – is divided into two irreconcilable ‘bodies’: her ‘natural’ body and her socially valued, exchangeable body’. The threat of women reclaiming their bodies poses a challenge to our central structures. Irigaray wonders what, ‘without the exploitation of the body-matter of women...would become of the symbolic process that governs society?’ If woman attains a status comparable or equal to man, her potential is equal, she is competition. For many, this unacceptable levelling requires a new distancing, so in the ‘market of sexual exchange’, Irigaray suggests women would then ‘have to preserve what is called femininity. The value of a woman would accrue to her from her maternal role, and, in addition, from her ‘femininity’’. Rather than real change, this looks more like a re-objectification campaign. Reacting to the question of Semenya’s femininity or perceived lack thereof, Noakes highlights the tension that suggests ‘if you don’t look like Angelina Jolie you’re not really a woman, and there are a vast number of women who are fed up with being told what they should look like – they interpret this as another male dominated intervention, where a female is being told what to do by men.’

Over the holidays I ran a pop-quiz past my friends: What is a woman? But reading Irigary I started to question my question and the choice of the word ‘what’ as it automatically assumes a position of objectification. Perplexed by my philosophical musing, a female friend said: ‘girls have vaginas, boys have willies...end essay’. Simone de Beauvoir’s 1949 introduction to The Second Sex starts with: ‘I hesitated a long time before writing a book on woman. The subject is irritating, especially for women; and it is not new. Enough ink has flowed over the quarrel about feminism; it is now almost over: let’s not talk about it any more. Yet it is still being talked about.’ And so it was I knew it wasn’t that simple, and talk more I must. At the back end of 2015 Caitlin (née Bruce) Jenner marked her womanhood with a full frontal lingerie shot on the cover of Vanity Fair and Lili Elbe (or Eddie Redmayne as The Danish Girl) marked his/hers as red-lipped coquette with come-hither eyes that seductively stared me down in an advertising campaign spread across the city. So, I thought, we’re looking at the camera (good), but must we look only if scantily clad and seemingly sexed? Is this what it has become to be a woman? This narrowing, a frightening detour from the initial liberating intentions of feminism.

Xavier Dolan’s splendid film Laurence, Anyways avoids similar stereotyping with a story that wades through the complexities of gender by focussing instead on the transformative effects of love and the transcendence of conformity in pursuit of a holistic, true, though probably ‘imperfect’ identity. Like the recent, much-hyped release, The Danish Girl, Dolan’s 2012 feature has as its protagonist, a male character who feels, knows he is a woman, but Dolan’s focus for Laurence and his transition has less to do with the familiar ‘feminising’ accoutrements, than the pursuit of an identity that reclaimed and revealed can be better met in relationships with colleagues, lovers, parents and friends. Professor of French and Literature at the University of Wisconsin, Tom Armbrecht, in a paper from 2013, calls Laurence, Anyways ‘a film about sexual identity, but without sex’ (un film sur l’identité sexuelle, mais sans sexe) and as such, says Dolan is able to explore trans-sexuality as a metaphor and focus on the effects of his ‘coming-out as a woman’ (aux effets du coming-out en tant que femme). For Laurence, the passage of another birthday as a man is a marker of yet another year living with death ‘a breath away’, living as he describes it: ‘under water’. Waiting to surface, he finally reveals to his girlfriend, Fred, ‘I can’t breathe...I can’t take it anymore. I’m dying.’ Armbrecht likens the dual desires of the gaze in the formation of the self – the need to perceive and be perceived – to the rebirth necessary for Laurence to become visible. He says: ‘the invisibility of even one part of the being, for example, sexuality, is indeed what, if oppressed, risks asphyxiation.’ (L’invisibilité de seulement une partie de l’etre, comme la sexualité, est si oppressante qu’elle risque de l’asphyxier.) In order to live, Laurence must change and be changed by his decision to pursue his truth. Though this change includes electrolysis, hormones, an earring, and a vague trace of make-up, these are not the most important components of Laurence as ‘woman’. She is strong, determined, she is up for a fight, she has a career, she’s a writer, an intellectual. She is, to his mother’s relief, still able to move the TV upstairs. Through Dolan’s use of significant relationships: Laurence and his girlfriend (boyfriend/girlfriend/friend/lover), Laurence and his mother (son/daughter), he’s able to emphasize what it is that is permeable and therefore constant – despite gender, despite sexuality – to delve deeper and discover what it is that’s unique in his/her being.

From here I’ll continue to refer to Laurence using she/her pronouns as she does in the film.

Amid her struggle for acceptance, Laurence faces dismissal from her position teaching literature. The school board buckles under pressure from a parents’ group determined to see her removed. They cite the inclusion of trans-sexuality as a mental illness in the DSM, suggesting she’s unfit to teach (this despite industry awards and accolades). She’s told that as she’s about to write a book, she should see this as an ‘opportunity’, to which she rebuffs: ‘In short, I should thank you for the gift of unemployment because, silly me, who needs an income when you work in the arts right?’ The injustice is echoed in Irigary where in Between East and West she writes: ‘It is thought to be normal, moral, a sign of good policy, for a woman to receive no payment, or low payment, to be asked to do charity work. Especially if the woman does intellectual work. Especially if she works for women’s liberation.’ And again in Sexes and Genealogies: ‘I am putting the two together: intellectuals and women. Their status is linked to an interpretation and an evolution of the mode of thinking and conceiving social organization’ which is to say – patriarchal, sacrificial.

Intellectuals, writers, women, women-writers, it doesn’t bode well. Of her practise as a writer and on her desires, Laurence reflects: ‘Can [they] be great enough to exempt one from the rejection and ostracism that affect people who are different? One who, in another time-space could be you or me?’ Speaking to a journalist on the publication of her book Head Above Water the interview takes a Freudian turn: ‘What do you want, Laurence Alia?’. She replies: ‘Someone who understands my language and speaks it... who will question not only the rights and the value of the marginalised but also those of the people who claim to be normal.’ Normal, mainstream, like what? You? Me? ‘Our generation can handle this!’ Fred exclaims enthusiastically, thinking she’s ready to share the transformative journey. But our generation – with their pink hair, tattoos, piercings – risks complacency. It’s best we don’t forget how the space was won, and the fact it’s not yet wholly safe, egalitarian. The project to procure rights isn’t over, and new forces are infringing previously made gains, or capitalising on them in bad faith – to make money, win power, influence people.

In South Africa, there is a rich history of human rights activism and the support team surrounding Caster Semenya proves there’s unfinished business. Intersex South Africa founder, Sally Gross, was previously an activist against apartheid. Her hopes for change are based on the belief that the South African experience provides a model for progress. She says: ‘Struggle against class-based oppression, against racial oppression, and against forms of oppression rooted in sex and gender, cannot really be teased completely apart; and, in a fundamental sense, liberation is not complete when any of these forms of oppression persists.’ Having been born into relative poverty, one of the lawyers who acted pro bono for Semenya, Benedict Phiri, likened her struggle to his: ‘I understand the story of a person who is marginalised. I was born into a family that lived in a back room.’ His efforts on her behalf, indicative of what Gross says is: ‘a moral obligation [of the liberation history and culture] to take the issue up and to ensure that law and practice afford the intersexed adequate recognition and protection in the context of a culture of rights’.

In her essay on 'Women, the Sacred and Money', Irigary further examines the role of women in a sacrificial society suggesting: ‘it is crucial that we rethink religion, and especially religious structures, categories, initiations, rules, and utopias, all of which have been masculine for centuries. Keeping in mind that today these religious structures often appear under the name of science and technology.’ The testing to which Semenya was subjected is exemplary of this scientific structure, which along with economic structures can still be deployed to subjugate women, despite advances and the evolution of self-determination. ‘Independence’ is still contingent to a degree on external, validating structures at best judgemental, at their worst – violent, abusive. Gross highlights real ‘fears for Semenya’s life in the context of gender-based violence, particularly increasing numbers of rapes and murders of black lesbians who transgress gender expectations. The 2008 gang rape and murder of South African lesbian soccer star Eudy Simelane is mentioned as a prominent point of comparison 'highlighting the violent hatred that accompanies gender non-conformity.’

As a woman who spent much of my adult life playing soccer, I am shocked and amazed that anyone could find the idea so threatening. I’m not a lesbian, perhaps it was assumed – still my person was only ever at risk of injury on the field – even then the risks were minimal, after all it’s only a game. Generally, I’ve been free to be me and though this may not fit an-other’s idea of ‘feminine’, I fail to see how the act of playing soccer, or sitting spread legged on a couch can make you a ‘man’ – as many claimed in comments following Semenya’s appearance on a South African chat show.

If part of Semenya’s problem is her elite physicality, and physical prowess – ie a male domain – then what of men who are physically less? Are they women? When Laurence expresses his need to be a woman it’s not because he has a need to be weak, subjugated or sexualised. For him – smart, strong and ‘woman’ are not mutually exclusive. True we live in times where free-to-air TV can screen The Black Lesbian Handbook and a women’s World Cup win makes front page news, but we musn’t forget the people at the periphery who make it all possible – without them we risk limits to our self-expression and the blandness of an authoritarian idea of belonging.

Don't be bland. Be terrifying, be terrific, live on the périphérique...

Remembering Petit-Jean

‘One day, then, as we were waiting for the moment to pull in the nets, an individual known as Petit-Jean…pointed out to me something floating on the surface of the waves. It was a small can, a sardine can…

‘One day, then, as we were waiting for the moment to pull in the nets, an individual known as Petit-Jean…pointed out to me something floating on the surface of the waves. It was a small can, a sardine can. It floated there in the sun, a witness to the canning industry, which we, in fact, were supposed to supply, it glittered in the sun. And Petit-Jean said to me “You see that can? Do you see it? Well, it doesn’t see you!”’

– Jacques Lacan

Let’s start with Jacques Lacan. That dead French philosopher, hard enough to read in French, harder still in translation; linguistic clarity and subtleties lost in lumbered franglo phrasing. So much so Žižek (the living) has written a ‘How To’ English-language reader, his contribution to a cottage industry that raises the veil, gets to the point – perhaps makes Lacan’s points for him. Taught that no self-respecting student relies on crib notes* (for that’s what these are), I persist with Lacan, the real, a list of confounding questions growing, but my inclination to pitch my own entry point to his postulates on psychoanalysis and associated philosophising, waning. Instead, I find myself turning my attention to the man, trying to understand him, as if he were my analysand – intrigued, concerned by his oft alluded-to lack, his ever present desires, distress. It dawns on me our vast differences; deduce that time, sex and socio-economic status necessarily determines differentiated interpretations, no less on key scenes from his seminal work on ‘the gaze’, second only in importance to his theory on 'the mirror stage'.

So I raise the topic of the gaze with a friend, to gauge its currency as a conversation starter. She’s taken aback, not sure we still talk about ‘the gays’, you know, what they’re wearing, where they’re cruising, as if ‘they’ were a thing to begin with. Spelling it out, she’s no less perplexed. Even with my pop-psychology explanation, her eyes did that other thing – the anti-gaze – they glazed over. I probed further, trying the story of the sardine can on other friends, the reaction going one of two ways: either met with – you can’t be serious, is this what you lot (philosophers) debate – or with a certain tickled, humoured knowingness. The humoured knowingness – much like my own reaction – is one that, not without its pretensions, reveres Petit-Jean our fisher-philosopher, finds the sublime in the sardine can’s affronting simplicity, and accepts the insignificance of the I; whether the I is in fact the you, the me, Lacan, or whoever it happens to be on the receiving end of ‘the joke’, in order to revel in the scene, relax into the moment and find in it some kind of reassuring return.

I don’t mean to diminish the seriousness with which I’ve approached Lacan’s work, but it’s true to say the sardine can speaks to me with a relevance, that the remainder of his contribution, though noted, can’t. I must confess an inability to fully understand his efforts on the ‘four fundamentals’: that is Freud’s four fundamentals of ‘the unconscious, repetition, the transference and the drive’ around which he developed his theses for a 1964 lecture series at the École pratique des Hautes Études in Paris. Born into a late 20th century knowledge structure at a time of rapid information deployment and hyper self-centredness, it’s perhaps a sign of the times that the ‘Grandfather of psychoanalysis’ and his pioneering case studies, as well as the works of his mid-20th century disciples, feel dated and a little laboured to me. A modern woman with the good fortune of being deposited into a framework of pre-existing analytic vocabulary – for which I duly credit Freud, Lacan et al – I’m much more ‘where now’ than ‘how did we get here’. It’s an approach. I don’t claim it’s the only or best approach.

I’m aware that dealing with a translation of a transcript of an oral presentation I should be forgiving and prepared to give the text a second (third?), closer read, but when dealing in fundamentals, I picture a certain pursuit of clarity on the part of the author, so find it surprising that there’s nothing resembling a bullet point in 276 pages of exposition. Still, when Lacan thinks, writes, reveals his thoughts, he is necessarily exposing and subsequently exposed. Reading between the lines, this process reveals something of an individual’s unconscious. For this reason I respect the risk taken by creatives, who are left vulnerable, open to assessment, inadvertently granting access to their uncensored self, contained in and betrayed by subtext. In Lacan’s telling of the story in which Petit-Jean is protagonist, we catch a glimpse of his anxieties. By focusing on his fish-out-of-water feeling, I fear he misses the richness in the scene and subsequently the opportunity Petit-Jean presents him with, to close the gap, both between them, and for him, to find himself and be one.

A peril of the canon is to face constant criticism, but despite my critique, I know full well ‘oneness’ isn’t easy. I harbour the feeling, and attendant guilt, of having sat on my brother in utero. But these nine months of phantastical foetal dominance are invalidated by reality. My brother is in fact the older sibling; bigger than me, smarter than me, he earns more money, has a wife, two kids, a mortgage, and a rather silly dog. It’s in twinning with him and separating from him, that my responsibility begins. Lacan highlights a common trait in Freud’s unconscious – which whether exposed through dream, parapraxis (a Freudian slip) or spontaneous wit – its ‘sense of impediment’, is key to its function, its potential as ‘discovery…of exceptional value.’ In this uncharted territory of the gap, where lack and desire congregate in contest, value may well be exceptional, but any discovery is to risk a potentially painful awakening, for which we’d no doubt like some other to be responsible.

From the moment of conception, that initial ‘coming together’, we experience separation. Cells duplicating, umbilicus cutting, mirror reflecting. Add to that Lacan’s chrysalis split in psychoanalytical development, which ‘invented by a solitary, an incontestable theoretician of the unconscious…is now practised in couples’. No longer both analyst and analysand, incapable of finding the cohesive self through self-reflection, we’re virtually programmed to delegate, outsourcing in keeping with a theory of ‘two’, a not unimportant stage, on which I’ll expand... We meet with a mirror and see an image, a reflection, a representation creating two: a self, and a self-image. We perceive a doubling in our number and stature – a dangerous derangement at too early an age to understand this unquenchable gaze that drinks in our image, feeds our ego, but leaves us with the hangover of an unshakeable otherness. An eventual coupling with something, someone ‘real’ as a result, a ‘real other’ at the very least, is to urgently pursue a ‘mirage of truth’, which is an improvement on, and possibly the best we can hope for after this initial, integral schism.

There’s no organ like the eye to affect our own otherness. Lacan uses the example: ‘I see myself seeing myself’ to reinforce its distancing effect. In comparison ‘I warm myself warming myself’ is corporal, whole, one. The eye and its perceptive function positions it both of us and outside us at once. In that it’s outside us, it’s open to manipulation and the influence of the public. Its being ‘in public’ and no longer of our private, discrete domain, it’s liable to adopt judgemental, self-conscious attributes. There is no longer our eye, our gaze, but the gaze of others – others’ eyes everywhere, even in our own mind’s eye. All this looking and being looked at renders the subject in a state of suspension. ‘From the moment that this gaze appears, the subject tries to adapt himself to it…’ and so starts the dance of the marionette, metaphorical strings attached. Without physical form, we cannot compare the gaze to other objects we’ve learnt to desire, we can’t buy, manipulate, dominate or discard it. Lacan says: ‘Of all the objects in which the subject may recognize his dependence in the register of desire, the gaze is specified as unapprehensible.’ We can try to comprehend and contain the gaze by seeing our-self seeing our-self, but try as we might, our focal point will continuously shift. Like a dog chasing its tail, we only end up running circles.

A young, energised Lacan took off on a journey to give it a go – who of us hasn’t tried? ‘It’s a true story. I was in my early twenties or thereabouts – and at that time, of course, being a young intellectual, I wanted desperately to get away, see something different, throw myself into something practical, something physical, in the country say, or at the sea.’ He finds himself in a boat off the Northwest coast of France, one half of a classic, comedic odd-couple. Lacan and Petit-Jean – what a pair!

Lacan goes looking for danger, willing to take risks in order to share in the excitement of a life he has romanticised; the realities of labour clearly foreign to him. The first hint of his anxiety comes in an aside about his companion: ‘Petit-Jean, that’s what we called him – like all his family, he died very young from tuberculosis, which at that time was a constant threat to the whole of that social class.’ ‘That’ social class. Different to, no doubt lower than his, he’s focused from the first on Petit-Jean’s otherness, which only heightens his own discomfort. Already threatened, it’s impossible for Lacan to take the sardine can to the same conclusion I do, to see it in the same light. He admits: ‘the fact [Petit-Jean] found it so funny and I less so, derives from the fact that…[I] looked like nothing on earth’ and ‘rather out of place’. His judgement of Petit-Jean, the transference of guilt, blinds him to the humour and possibility to be in the moment. Lacan complains: ‘But I am not in the picture.’ His admission betraying a lack he cannot bridge by desire alone. Trying to control the situation and wrangle it into a framework he understands, he fails to grasp Petit-Jean’s gesture. When Petit Jean points to the sardine can floating past the boat, glittering in the sun and says: ‘You see that can? Do you see it? Well it doesn’t see you!’ I rather interpret it as his giving Lacan permission (fisherman to fisherman) to really be there with him, to chill the f*** out, and less as a psychoanalytic jibe over which to obsess.

Lacan being Lacan is at sea in this scenario. He’s in Sartre’s park. He’s not alone, and he doesn’t like it. ‘The depth of field’ he says, ‘with all its ambiguity and variability…is in no way mastered by me.’ Petit-Jean, the sardine can, they’ve thrown him off-centre. But the error is his. The need for mastery is a trap, a trick, which ego aside, lacks any real meaning. Lacan’s ‘colophon of doubt’ reinforces the Freudian extension of Descartes’ cogito: ‘I doubt therefore I think, I think therefore I am.’ It’s his doubt that creates ‘the stain, the spot’, and he emerges from the shadows in true intellectual fashion with theories that do little more than distract. The paradox is, this white noise widens the gap between him and Petit-Jean; Lacan falls victim to his own theory: ‘In so far as the gaze, qua objet a, may come to symbolise this central lack expressed in the phenomenon of castration, and in so far as it is an objet a reduced, of its nature, to a punctiform, evanescent function, it leaves the subject in ignorance as to what there is beyond the appearance, an ignorance so characteristic of all progress in thought that occurs in the way constituted by philosophical research.’

So less philosophising? Or a new philosophy?

At least let me retell the story...

Once upon a time we were one. Some time passed. Then came what now seems a quaint 20th century concern that we are in fact two, that the point from which we yearn for return is from the binary, the dual (man/woman, heaven/earth, good/bad). Today, in the 21st century, the issue is I am all too often everywhere, all at once. If the additional image of the mirror stage broke down the self into binary component parts: mind/body, self/image, presentation/representation, what of the self now we look, see and perceive ourselves in all manner of spatial and temporal locations at the same time, all the time? The world is awash with my image, a multiplicity of me swamping any coherent sense of my self. We’re everywhere and nowhere, we’re self-aware and self-conscious. Polyoptic, we’re all-knowing seers with the subsequent, myriad responsibilities. But as it’s all puffery, it’s no wonder we’re failing. Dismally.

Whereas once the philosopher drew the conscious on an adventure into the unconscious, today we’re tasked with bringing relief to a people (I’d say the West, but that’s too limiting, because data/bits have bifurcated globally) that for the most part exist in a supra-conscious space. All I want, given the impracticality in seven-plus billion of being by myself, is an opportunity to be with myself, to find a moment of insignificance among the hubbub. Those moments that remind me it’s not on me.

Were I in that boat with Petit-Jean, I would have taken his words and that singular moment of the waves, sun and lone sardine can in all its glittering glory, and let it float on by. I probably would have laughed a little to myself, nothing gregarious – then sensed the return – the relief that I could be here and here alone, and that there was nothing in the world that was needed from me, nor that I could do, to make any lick of difference.

Rather than drawing its attention to me, it serves to bring me back, to notice the natural – the waves, the horizon, the sublime – situating me, dwarfing me so much I forget misguided imperatives and elevated self-importance and reconfigure my smallness as the needing to be nothing but one. Lacan in comparison is on high alert, already exposed as an other in relief with Petit-Jean’s otherness. The irony is, it’s Lacan’s distancing look that creates the provocation and results in the threat of and need for an exchange in order to engage. ‘The world is all-seeing, but it is not exhibitionistic – it does not provoke our gaze. When it begins to provoke it, the feeling of strangeness begins too.’ The ‘who started it’ cycle begins, and Lacan fears he’ll be left hanging in an unmet gaze exchange like Sartre’s ‘point of nothingness where I am’. In comparison, Lacan favours a proactive grasping, an attainment of the gaze exchange that forces the other, or the object, to participate. But what would have happened that day if the sardine can had looked back?

If the sardine can saw me, it would accuse. A look after all is hardly ever free from judgement, expectation. And so begins the whirlpool: should I fish the can out of the sea to reuse? Recycle? Should I pre-empt the future of fishing – an unsustainable growth industry – and warn Petit-Jean that small-scale operators will soon be put out of business by super-trawlers? Should I question my moral position as carnivore, my distance from the realities of the catching, killing, transporting, canning, disposing. Should I deride human behaviour, its consumption, waste and adverse impact on the planet?

Or do I accept this instance of the sardine can fashioned as stupa, rock cairn – a punctuation in the landscape? All across the vast mountains and plains of Central Asia and beyond, you find a human trail of meditative breaks that bring greater attention still to the surrounding, sublime landscape. Four, five, six small stones in a balanced pile, here, there, bring you into that moment, in to nature, to look at it, be in it, recognise in its expanse, that you are allowed to be small, adequate in your ability to only ever do justice to one. If we recognise and allow the sublime to overwhelm our emotions, we neutralise the self. If Freud’s to be believed, men don’t deal well with ‘neutering’, equating it with castration. But for the rest of us, or for everyone dealing now, with the more pressing issue of an over-abundance of knowledge, responsibility, and an obliteration of the self into myriad – sometimes schizophrenically incongruent – representations, it serves to at least put us back together. Neutral, now, is nothing to fear. We need to return to that space so we can begin again and do better this time.

When I need to, I think of China, and everything is ok. China is a mess. Polluted, epic, incredible. I can’t do anything about China. China has no interest in me. Sometimes I go to the coast and look at the ocean. Waves, walls of water, do what they will. They’re refreshingly unconstrained and from time to time demonstrate their destructive disinterestedness. When I see the ocean, I am on my own, not lonely, but one, with my self.

In a video from 2015 on the Guardian website, sculptor/artist Antony Gormley is filmed walking through Kings Cross, London, an area once home to a number of squats used by artists as studio space. Pointing to a building he once worked from he says: ‘22 artists worked there for nearly seven years, entirely free, how things have changed.’ He bemoans the city’s rampant commercial development that’s outpricing artists, students and the necessary ‘fresh blood’ needed to keep a city multi-faceted and moving forward culturally. I can testify to the truth in this claim. A city of 8.6 million, competition and consumerism is rife, capitalism is king and with leaf-free trees three-quarters of the year and a grey, working city river there’s little to stop you getting swept up in it all. As Gormley’s prospects improved, the artist commissioned a purpose built studio where his criteria for the architect were: ‘light, space, silence’, elements just short of the miraculous in central London. Lucky for him. For the rest of us, Gormley performs a community service, drawing attention to the key feature the city still shares which encompasses all three. Describing his art in the video as ‘a catalyst for making people aware of how extraordinary their lives are already’ his 2007 exhibition, Event Horizon, positioned life-sized casts: ‘indexical copies of my body…[which] in their displacement of air, indicate the space of “any” body; a human space within space at large.’ The bodies, installed on building tops across the city of London and staged later in cities like Sao Paulo, Hong Kong and New York, and in the Austrian Alps, created ‘acupuncture points…[that]… ask us to attend...’

‘Through the agency of this body I will become aware of the sky.’

Gormley hoped that through ‘this process of looking and finding, or looking and seeking, one [would] perhaps re-assesses one's own position in the world and become aware of one's status of embedment.’

And the first place in which we are embedded is in us, our bodies.

The sardine can, rock cairns and Gormley’s statues all draw attention to the natural environment, that expansive place where one’s individual nature is its most apparent. Rather than overwhelming, the sublime reduces the need for the subterfuge of knowing and the responsibility of doing something with that knowledge; creating space for humour and non-knowing. Along with the rapid multiplication of images and diminution in their value in the late 20th and early 21st century, information and subsequently the virility knowledge, has suffered a similar fate. There is now all this stuff we know. Stacks of it. I could say on the one hand, I know more than Socrates: I know the earth is round, e=mc2, the lyrics to Ice-Ice Baby, and who killed Laura Palmer. You couldn’t disagree. Nor would Socrates, modestly admitting: ‘I know that I know nothing’. But my knowledge is a ruse. What I know lacks body, teeth, and other transmogrifying features. More valuable right now would be a shift in focus onto what Sarat Maharaj calls ‘avidya’, Sanskrit for non-knowledge or ‘productive confusion’ and to accept that without the stages of contemplation and self-discovery, my broad but cursory general knowledge won’t stand up to prosecution. In Anthony Huberman’s 2009 artist book – a collection of the non-knowing, titled: For the blind man in the dark room looking for the black cat that isn’t there, he references the cabinet of curiosities as an example of non-knowing ‘[once,] people simply enjoyed the experience of not knowing and not understanding’, but in the demystified world of wikipedia, their effect is diminished, their wares, dusty. Opportunity to stop and reflect in a fast world now to be found in the form of grandiose artworks like those by Olafur Eliasson and Anish Kapour whose vision and budgets combine to awe the individual.

Olafur Eliasson, describing his works on his website as bringing ‘body consciousness’ through manipulation of a person’s journey and orientation in the spaces he creates. He’s interested in subjectivity and sensation, personal qualities of a present, embodied self. For Olafur Eliasson Studio colleague, Anna Engberg-Pederson, the new utopia is a wunderkammer that operates like a miniature parliament: ‘a place intended for people to get together and negotiate the conditions for thought.’ Free from the sameness (an imposition) of a modernist utopia, the difference is in diversity and scale and the delegation of discussion ‘to each household, university, city or society’. The line between body-consciousness and self-consciousness is crucial to maintain, and works like The Blind Pavilion (Venice Biennale, 2003) Din blinde passager (ARKEN Museum of Modern Art, Copenhagen, 2010) and The Weather Project (Tate Modern, London, 2003) tread a fine line. Self-consciousness risks an unhealthy heightening and conglomeration of all our anxieties, whereas a body-consciousness is a proactive pursuit akin to the philosophy of Georges Bataille who: ‘active in Surrealist circles in Paris in the post-war period…pushed the limits of decency and resisted the oppressiveness of moral idealism. At the core of his work was his total embrace of the experience of not-knowing, and while [Alfred] Jarry considered it a cause for laughter, Bataille would go further and claim that to not-know would be to experience the religious and the sublime. He would call this thing, non-knowledge, using the term that places not-knowing inside the fabric of knowledge, not outside of or in contradiction to it.’

In other words, get over yourself.