Something like a phenomenon

To date this piece, I write at the time of the worst ever domestic shooting in the US. Which at the time you’re reading, may not be the worst anymore. As it is, I’ve got 49 dead, 53 wounded.* What have you got?

If, phenomenologically, I feel my way through the news as it is, it feels pretty shit. Get bogged down in causal categories of history, psychology, sociology – it’s shitter still. Project into the future, and I'm inclined to the morose, musing what’s it all for (this thing called life) when it’s only getting worse? So phenomenology – the dealing with the phenomena – the things, objects, people, affects as they are, now has its appeal even if only as the best of a bad bunch of ways to work through the world as it is for us, now.

The existentialists, confronting existence and engaged in a life-long, laboured search for meaning, rely on phenomenological experience as some kind of consolation to the delayed gratification of death. In the long interim called life, in which we inhabit a body, some decamp to nihilism, some to absurdity (which is possibly just an optimistic rebranding of the former). And so it is, without a more appealing alternative, accepting the absurd and embarking on the existential project has become a way of experiencing, interpreting, advancing, and at times transgressing the world as I’ve found it.

The present of a person reading this essay will occur in an infinite now. This text will appear as a collection of letters which I ask you to confront in the spirit of phenomenology. In so doing you’ll find clues to the direction of my philosophical inquiry, a methodological approach to my thinking, and a determined effort to overcome cynicism by subsuming resonance from other people’s projects, using the momentum to run interference of my own. So come closer, join me.

I’ve done my time from afar. I’ve lived and read, and as I’ve read – as a woman – I’ve been disinclined to fret about the universal use (I’m being generous) of ‘man’ for human, of which I, as woman am part. The overwhelming abundance of man/he/himself/his has in fact helped me maintain a distance from which I can think abstractedly about what I read, to learn in isolation from the encumbered self. So finding a way for it to suit me somewhat (possibly the worst kind of collaborator) I hadn’t previously taken up a political or feminist stance on the issue, choosing to see it (even defend it) as a linguistic device deployed for the sake of simplicity. But now I have my grounding, I’m ready to move past abstracts and dive in.

Where I now encounter/perceive the use of man/he/himself/his as simplistic, thoughtless, anachronistic or lazy and not necessary to denote the male in opposition or exclusion to the female, I alter it to read respectively, the personally relevant woman/she/herself/her. This way, I have begun to bridge the gap that remains between the ideas and my prescribed and identified female self. But this personal project must become more than a private habit and more broadly influence the feminist linguistics project which certainly is political in its pursuit and potential to better the world (and which may be surpassed by a circling trans-linguistic theory before it’s fully realised – all the more luck to it!).

I want to be clear men are not the problem (she tells herself). I am a prolific reader, supporter and believer of the many men who know what to do with their manhood. The problem is privatisation, professionalisation, industrialised military and security, and the stranglehold capitalism and the corporation has on government, the judicial system, media and religion. The problem is that all these things are inherently mean and nasty. And it just so happens, in the western-historical tradition, they’re problems most commonly peopled and propelled by men. Granted, it’s for the same western-historical reason that men have led much of the critique and resistance (and which possibly explains why the revolution has never looked quite different enough to effect change).

From within the university, a one-time fertile place for freedoms and possibility, the view is similarly bleak. In an update of Michel Foucault’s ‘disciplinary societies’, which mapped the penetration of panoptic- and bio-power into everyday life, Gilles Deleuze stresses a more invasive shift to complete control: ‘just as the corporation replaces the factory, perpetual training tends to replace the school, and continuous control to replace the examination. Which is the surest way of delivering the school over to the corporation.’

Infantalised, (the irony being we pay for this patronage) we can abide by the fantasy, fight it, flee or free-fall between the gaps to Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s ‘undercommons’ of the university. They write: ‘it cannot be denied that the university is a place of refuge, and it cannot be accepted that the university is a place of enlightenment. In the face of these conditions one can only sneak into the university and steal what one can. To abuse its hospitality, to spite its mission, to join its refugee colony, its gypsy encampment, to be in but not of – this is the path of the subversive intellectual in the modern university…The subversive intellectual came under false pretences, with bad documents, out of love. Her labour is as necessary as it is unwelcome. The university needs what she bears but cannot bear what she brings. And on top of all that, she disappears. She disappears into the underground, the downlow low-down maroon community of the university, into the undercommons of enlightenment, where the work gets done, where the work gets subverted, where the revolution is still black, still strong.’

In a country that is not my own (the UK), I’m begrudgingly welcomed on account of my money, my pink complexion, and my capacity to perform all manner of box-ticking tasks. I wish I could be, I know I should be, but I’m not happy. Like other performances, I hoped there was a threshold beyond which (striving) would end and the real project (living) would begin. To save being sucked into permanent performance I think of Roberto Bolaño’s ill-prepared protagonist – and narrator of his short novel, Amulet – Auxilio Lacouture. Her story unfolds in the 12 days she’s alone in a bathroom at Mexico’s National Autonomous University during the 1968 army occupation. Strange to look to a fictional character with few teeth left in her mouth and little flesh on her bones for inspiration, but her unshrinking honesty, precariousness and jouissance despite it all, are refreshingly real.

On leaving her native Uruguay she recalls: ‘one day I arrived in Mexico without really knowing why or how or when. I came to Mexico City in 1967, or maybe it was 1965, or 1962. I’ve got no memory for dates anymore, or exactly where my wanderings took me; all I know is that I came to Mexico and never went back…Maybe it was madness that impelled me to travel. It could have been madness. I used to say it was culture. Of course culture sometimes is, or involves a kind of madness. Maybe it was a lack of love that impelled me to travel. Or an overwhelming abundance of love. Maybe it was madness.’

In the poetry of the sad, desperate, young Mexican poets, she seeks and finds her figurative reflection. She also finds herself literally, tragi-comically on the toilet – underwear around her ankles, reading the poetry of the melancholic Spanish exiles she admires – as the army invades.

‘I am the mother of all the poets, and I (or my destiny) refused to let the nightmare overcome me. Now the tears are running down my ravaged cheeks. I was at the university on the 18th of September when the army occupied the campus and went around arresting and killing indiscriminately. No. Not many people were killed at the university. That was in Tlatelolco. May that name live forever in our memory! But I was at the university when the army and the riot police came in and rounded everyone up. Unbelievable. I was in the bathroom, in the lavatory on one of the floors of the faculty building, the fourth maybe, I’m not exactly sure. And I was sitting in a stall, with my skirt hitched up, as the poem says, or the song, reading the exquisite poetry of Pedro Garfías, who has already been dead for a year (Don Pedro Garfías, such a melancholy man, so sad about Spain and the world in general).’

And as the soldiers search the university and the first day of the occupation comes to a close, she declares: ‘I knew what I had to do. I knew. I knew that I had to resist. So I sat down on the tiles of the women’s bathroom and, before the last rays of sunlight faded, read three more of Pedro Garfías’s poems, then shut the book and shut my eyes and said: Auxilio Lacouture, citizen of Uruguay, Latin American, poet and traveller, resist.’

Her experience is truly and fantastically devastating to aspirations of order and reason which, frankly, have failed to combat or explain the ridiculousness of reality. Her resistance is as much a testament to accepting this fact, as it is an embrace of chaos. I say this as someone whose inherited, intellectual framework is distinctly Kantian. I love a category. Like ‘cleanliness is next to godliness’, organisation is the closest I come to religiosity. I’m so inclined to the theoretical foundations of ‘practical reason’, I consider it a given and tend to dismiss Kant as a result; for what is a given doesn’t need an author or a grand design. Surely, along with other chromosomal information, it was deposited from my family into my very being...

But to excel at the application of the rational is to eventually nullify the individual. The hyper dialectic of the malleable rationalist is a conversation with myself where I argue all sides; over time, becoming so convincing at playing the different parts – seeing every point of view – my personality becomes disembodied, distanced, and argument and counter argument reduced to formula, detached from their substance or sensory tenor.

‘The surrender of woman’s thinking to rationalism and of her artifice to technics have consequences which console woman with the feeling that she is progressing, but make her neglect or deny fundamental forces of her inner life which are then turned into forces of destruction. “The sclerosis of objectivity is the annihilation of existence.”’ (Mairet/Jaspers)

…that was then.

Life’s not like that. After all, how does Kant help us make ‘individual human decisions’? And where will ‘detached deliberation’ get us? The critical dilemmas for an individual can’t be solved with the facts and laws of how to think through them. Resolution comes from ‘conflicts and tumults in the soul, anxieties, agonies, perilous adventures of faith into unknown territories.’ (Kierkegaard)

The first revolt (already an atheist) has therefore been against myself. My life was ‘pitched into the drift of phenomena’ where, abandoned, ‘the only hope for woman lies in her full realisation and acceptance of the truth [that that’s the way it is]…her personal fate is simply to perish, but she can triumph over it by inventing “purposes”, “projects” which will themselves confer meaning upon the self and the world of objects…There is indeed no reason why a woman should do this, and she gets nothing by it except the authentic knowledge that she exists.’ (Heidegger/Jean-Paul Sartre)

Existence can be a challenge when building an identity from the ground-up, inside-out, rather than opting for a ready-made. Thrust into uncertainty as the process plays out, despair can circle, as: ‘not many are capable of authenticating their existence: the great majority reassure themselves by thinking as little as possible of their approaching deaths by worshipping idols such as humanity, science, or some objective divinity.’ (Mairet)

Equally unmoved by Dawkins, Beyoncé and ‘God’, I’m happy to accept that ‘woman is nothing else but that which she makes of herself.’ (Sartre)

But bearing the responsibility of working out what that ‘else’ is, a detour via nihilism is an unsurprising turn, and for Nietzsche in The Will to Power, completely necessary: ‘because the values we have had hitherto thus draw their final consequence; because nihilism represents the ultimate logical conclusion of our great values and ideals – because we must experience nihilism before we can find out what value these “values” really had – we require, at some time, new values.’

Wise words. I lived for a time in a share house where amid the unpaid bills, tacky magnets and cleaning rota, the fridge bore a sticker: ‘try being informed instead of just opinionated.’ Philosophy (for the etymologists, philosophia – Greek, love of wisdom), may prove useful in this pursuit: to research, unearth and re-evaluate ideas. Plotnitsky writes that philosophical confrontation: ‘entails an affinity and alliance with chaos’ so as to confront mere ‘opinion’ which serves only ‘to protect us from chaos’.

We live in an age of opinion, which at one time I lauded as egalitarian. But ideas that bounce around between various opinions cannot be changed by those opinions. Opinions only add noise to the chaos, whereas: ‘philosophy engages with chaos through the creation of concepts and planes of immanence; art through the creation of sensations (or affects) and planes of composition; and science through the creation of functions (or propositions) and planes of reference or coordination.’ (Plotnitsky)

Phenomenology, a confrontation of perception, not preconception, could help put opinion to one side, forcing a pause, which unlike mindless opinion, over-thinking (a tendency of mine) or random acts, provides the time for philosophy to enact an idea.

All ideas? In any situation?

I’ve asked myself the same questions. Alain Badiou’s ‘philosophical situation’ favours the ‘incommensurate’ over the ‘commensurate’, citing the incommensurate as one where there’s a choice: ‘philosophy confronts thinking as choice, thinking as decision. Its proper task is to elucidate choice. So that we can say the following: a philosophical situation consists in the moment when a choice is elucidated. A choice of existence or a choice of thought.’ To situate, or measure the gap in the incommensurable: ‘we must think the exception. We must know what we have to say, about what is not ordinary. We must think the transformation of life…[and we must do so] against the continuity of life, against social conservatism.’

The distance between power and truth can be traversed by philosophy without devolving to opinion (which given it thrives on volume and exposure is even more dangerous when pronounced by the wealthy and privileged). Echoing Zizek’s ‘false alternatives’ Badiou outlines where he can and cannot do more than opine. An election, for example: ‘does not create a gap, it is the rule, it creates the realization of a rule.’ It’s institutional. A government and its opposition are commensurable, and therefore isn’t ‘a situation of radical exception’, and elections by turn, no turf for the philosopher. I want instead to debate the terms of the election, its currency, its potential, its evolution (and subsequently – revolution). This could explain how I turned away from politics as it is, while remaining political. The something more than it is, is posited within the ‘project’, and though my project doesn’t resemble a campaign, it is inherently political in a way that can’t be institutionalised or owned by any single interest group.

A revolt that resists both nihilism and opinion can be hard going. Like Albert Camus I’m inclined to ‘the meaning of life [as] the most urgent of questions’, but paradoxically, given it’s the great unanswerable, the more difficult thing to do is judge ‘whether life is or is not worth living’ without the definitive (or a priori) rights and wrongs to guide us.

‘Living, naturally, is never easy. You continue making the gestures commanded by existence for many reasons, the first of which is habit. Dying voluntarily implies that you have recognized, even instinctively, the ridiculous character of that habit, the absence of any profound reason for living, the insane character of that daily agitation, and the uselessness of suffering.’ (Camus)

But this isn’t an invitation to give up. Quite the opposite. The optimistic spin Camus and Sartre gave existentialism (the absurd, coffee) is naturally appealing and an improvement on the alternatives (suicide, fascism). For Camus, the ‘divorce’ between ‘the person’ and ‘their life’, from the most testing to the most banal of circumstances, is ‘the feeling of absurdity’ and he suggests that like war, the absurdity of life cannot be negated: ‘One must live it or die of it. So it is with the absurd: it is a question of breathing with it, of recognising its lessons and recovering their flesh. In this regard the absurd joy par excellence is creation. “Art and nothing but art,” said Nietzsche; “we have art in order not to die of the truth.”’

And the truth is we will die. Japanese conceptual artist On Kawara passed away in 2014. In 2015 the Solomon R. Guggenheim Gallery, New York staged a survey of his life’s work. Unknown to me at the time, I entered the gallery off ice, salt and mud strewn streets for the swirling architecture, the promise of Kandinsky’s Reifrockgesellschaft, and central heating.

fig. 1

What I got was much, much more. Over a year since, I’m still intrigued by my encounter with On Kawara’s body of work, back tracking through exhibition ephemera and show catalogues for clues to his life and reasons why it has struck such a chord. For an artist of whom there’s no picture, he’s more familiar to me now than the over-saturated Andy Warhol. Having moved to New York in 1965, Kawara’s practice unfolded in the same place and similar period as the savvy pop-artist (whose work I also admire, but for very different reasons). Eschewing photography and video, Kawara instead marks the boundaries of his body through an ongoing project of presence.

The Heideggerian Dasein comes to mind; the term a German construction of da (there) and sein (being), tidily combining notions of existence, in time, spanning Heidegger’s humble ‘thatness and whatness’ and Hannah Arendt’s assessment of Existenz, of which she says: ‘we are all ourselves little Gods after Heidegger.’ I don’t disagree with Arendt. The God complex poses a challenge, particularly when combined with dog-eat-dog capitalism, and people who equate more money with ‘more right’, but Heidegger proposed something altogether more grounded:

‘Not only does an understanding of Being belong to Dasein, but this understanding also develops or decays according to the actual manner of being of Dasein at any given time; for this reason it has a wealth of interpretations at its disposal. Philosophical psychology, anthropology, ethics, “politics,” poetry, biography, and the discipline of history pursue in different ways and to varying extents the behaviour, faculties, powers, possibilities and vicissitudes of Dasein…The manner of access and interpretation must be chosen in such a way that this being can show itself to itself on its own terms. Furthermore, this manner should show that being as it is at first and for the most part – in its average everydayness.’

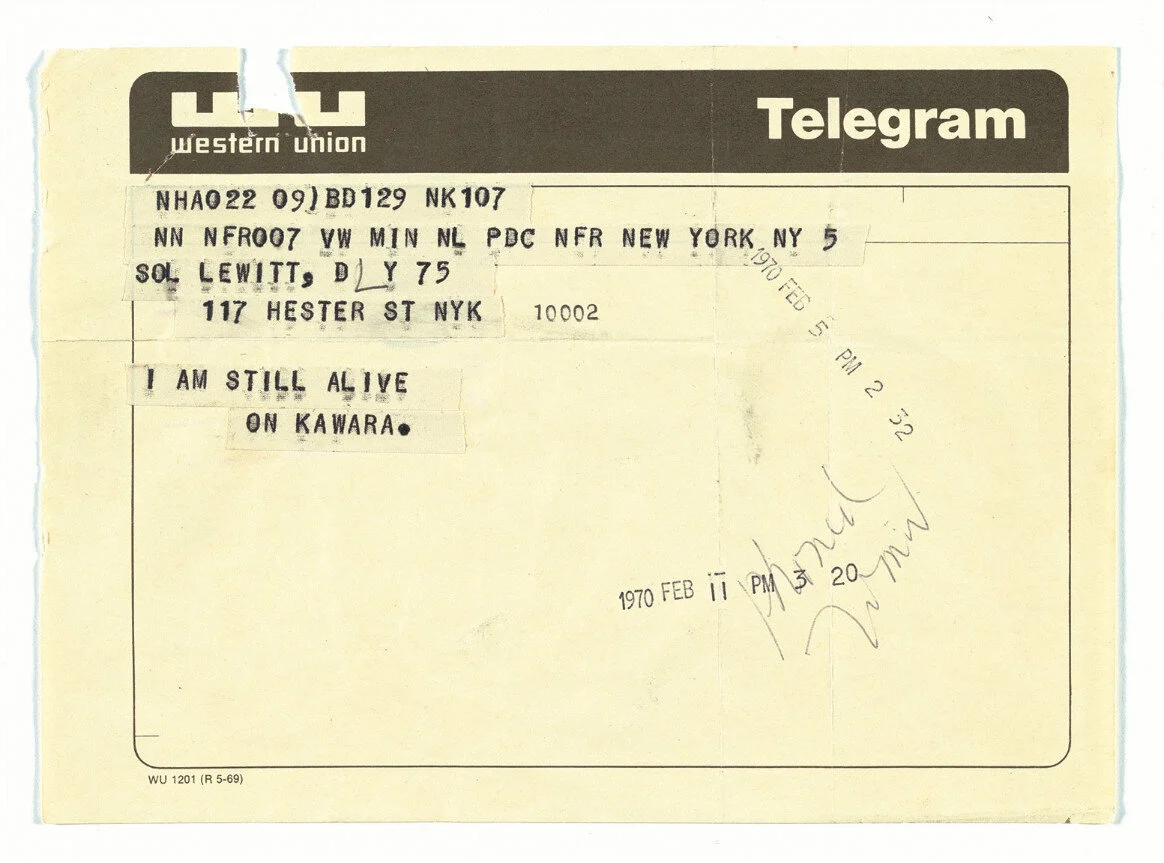

The everyday was something Kawara lived with unusual commitment. In his Date Paintings (the Today series), and companion series – I Went, I Met and I Got Up At, Kawara meticulously makes traces of his everyday existence. His long-running series I Am Still Alive, consists of telegrams sent from the many, many places to which he travelled, conveying the single statement to friends: ‘I am still alive’.

fig. 2

This alternative, experimental biography ‘relies on an objective sensibility, not an analytic one: no attempt is made to register impressions, anecdotes, opinions’ which like phenomenology ‘declines to explain the world, it wants to be merely a description of actual experience. It confirms absurd thought in its initial assertion that there is no truth, but merely truths.’ (Camus)

Situating his broader practice at ‘the exact point of intersection between the objective and the subjective’ (catalogue) I’m inclined to draw parallels from this midpoint to the territory, long-revered in Buddhism, of the middle path – of mindfulness – where the reconciliation of dualisms occurs in the relationship between the self and the external world, in a balance between the two.

Growing up in a timezone more closely associated with Asia, and in a time period when those immigrating to Australia came mainly from the Asian continent, my influences and subsequent outlook angle as tangentially East as they do West – perhaps explaining something of the resonance with and recognition of this space. Meditation has helped put the body back into I am, in an attempt to recover from the mind/body split. There is no art form as potentially effective as dance to do the same. German choreographer, Pina Bausch is described as creating contemporary dance pieces: ‘that deal with those basic questions about human existence which anyone, unless she’s merely vegetating, must ask at least from time to time. They deal with love and fear, longing and loneliness, frustration and terror, man’s exploitation of man (and, in particular, man’s exploitation of women in a world made to conform to the former’s ideas)…’

But even dance has been subjected to rules, and is at risk of becoming a formulaic, constrained ‘performance’. In an interview, Bausch asks: ‘Why do we dance in the first place?’ And warns: ‘There is a great danger in the way things are developing at the moment…everything has become routine and no one knows any longer why they’re using these movements. All that’s left is a strange sort of vanity which is becoming more and more removed from actual people.’

Less interested in how people move, Bausch focused her attention on what moves people – allowing the body to speak. Contrary to criticisms of phenomenology’s introspection, new methods of connection and communication support the potential for phenomenology to promote action and agency. Merleau-Ponty metaphorically links the ‘synthesis of one’s own body’ to our perceptive faculty and Leder expands on the binding capacity of ‘phenomenological vectors’ linking their function to a method of meaningful engagement with the world. As Plotnisky points out: ‘There is no concept with only one component. Each concept is a multi-component conglomeration of concepts, figures, metaphors and so forth which, however, have a heterogeneous, if interactive architecture rather than forming a unity. Concepts are junctures rather than sums of parts. They are forms of vibrations and are defined by resonances, through which they may amplify or temper each other.’ (after Deleuze and Guattari)

At each juncture, there’s a fork in the ontological source code: ‘Resonance frequencies of a given conceptual system may be “awakened” by a driving force coming from another system or two such systems may be in resonance. This is, again, an interference-like process which makes the systems “vibrate”; makes them literally more “vibrant” in a convergent or divergent fashion.”

Vibration might well describe what I felt when reading Roberto Bolaño, when faced with On Kawara’s artwork, and while watching dance choreographed by Pina Bausch. A serious defence of ‘the vibe’ suddenly doesn’t seem so absurd. The much-loved 1997 Australian film, The Castle, includes a courtroom scene where protagonist Darryl Kerrigan’s hapless Barrister gives an often-quoted closing speech in support of his client’s submission to save his house from an airport expansion project.

Hapless Barrister: ‘It’s the constitution, it’s Mabo, it’s justice, it’s law, it’s the vibe, and ah no that’s it, it’s the vibe.’

[A beat.] ‘I rest my case.’

Darryl Kerrigan: ‘That was sensational.’

The argument is surprisingly effective, with the judge ruling in their favour, Kerrigan king of his ‘castle’.

Another closing speech – in which I’d make the case that the first thing I must do to implement my philosophical methodology is live. And to be alive is to continually question and create meaning for myself. By adopting a phenomenological posture I avoid over-thinking and prejudice, and provide the optimum conditions for the necessary resonance to take affect. The interference may be uncomfortable and the result, a wholesale shift in understanding, but on the flip-side, it could be thoroughly pleasant and the project a success. While I work on it, let’s just say I see things how I see things, and I call it how I see it, and how I see it tomorrow may change from today, but tomorrow when I see it, well – stay tuned…

Notes:

*12 June 2016, Pulse nightclub, Orlando, Florida. May the 49 killed rest in peace; may something be done about guns.

As Rage Against the Machine sang in the 1998 track No Shelter: ‘The front-line is everywhere.’

Sartre defends the existentialist movement as humanist on account of the political and religious ambiguity of existentialism. Due to its indeterminate nature, it provides a forum for people from all quarters to meet and discuss human problems of primary importance and common concern.

Reifrockgesellschaft might sound like a track by Rammstein, but translates as Group in Crinolines.

From the foreword to an On Kawara exhibition catalogue: ‘No artist’s statement here, as ever, no portrait of the artist and no interview.’ (Gautherot and Watkins)

‘Dostoevsky once wrote “if God did not exist, everything would be permitted” and that for existentialism is the starting point.’ (Sartre)

Unlike Daniel Dennett’s negative assessment of introspection (‘failures of imagination’) I’m inclined to liken it to the calm before the storm – as a necessary and valuable component of the storm itself.

And if it is absurd, may I defer to Camus…‘I draw from the absurd three consequences which are my revolt, my freedom and my passion.’ (Myth of Sisyphus)

fig.1

Vasily Kandinsky

Group in Crinolines, 1909, Oil on canvas

37 1/2 x 59 1/8 inches (95.2 x 150.1 cm)

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection

© 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

fig.2

On Kawara

Telegram to Sol LeWitt, February 5, 1970

From I Am Still Alive, 1970–2000

5 3/4 x 8 inches (14.6 x 20.3 cm)

LeWitt Collection, Chester, Connecticut

© On Kawara. Photo: Kris McKay © The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York